OU researchers discover complex effects of temperature shifts on both hosts and parasites

While climate change is often associated with global warming trends, it is also believed to influence patterns of temperature variability, with greater and more frequent shifts in temperature from one day to the next. Those temperature shifts could change the way certain species interact with each other.

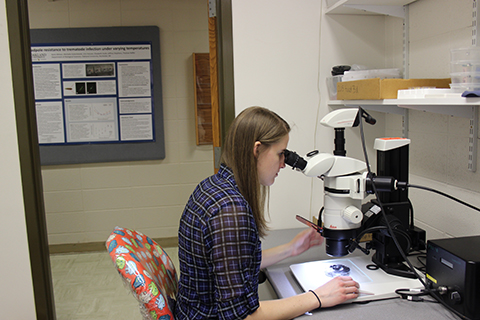

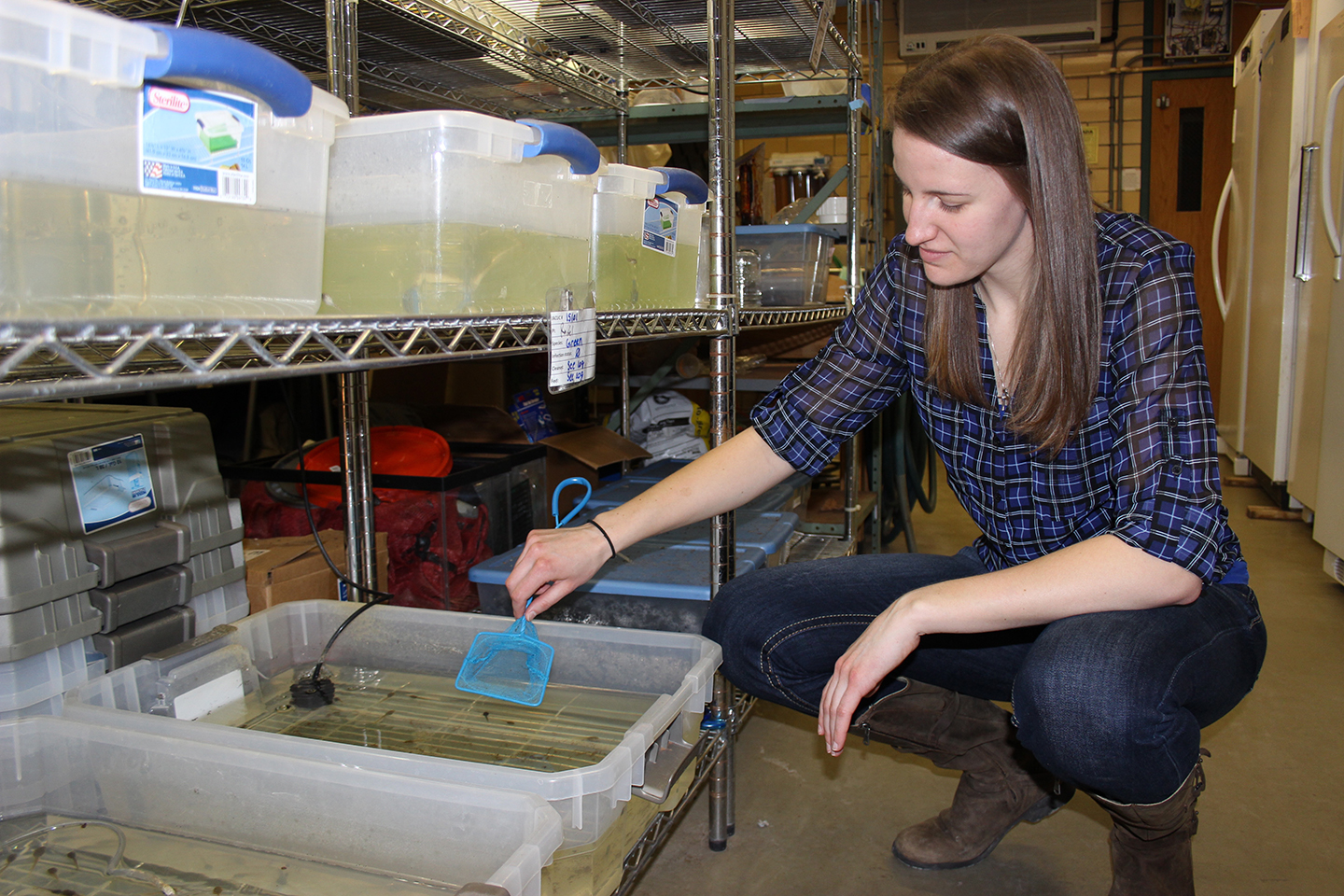

Karie Altman, a fourth-year student in Oakland University’s Biological and Biomedical Sciences Ph.D. program, has been investigating the effects of temperature variability on host-parasite interactions.

Working with OU biology professor Thomas Raffel, and a team of undergraduate students, Altman conducted experiments in which tadpoles were exposed to flatworm parasites following an abrupt increase or decrease in temperature. The goal of the research was to find out how these temperature changes influence host-parasite interactions.

“We acclimated each tadpole to a given temperature for three weeks,” Altman explained. “After that, we exposed the tadpoles to a flatworm, and changed the temperature. We kept checking to see if the parasites remained with the tadpoles, or if the tadpoles’ immune systems were able to clear the parasites.”

Altman worked with a team of OU researchers, whose findings were recently published in the "Journal of Animal Ecology." |

The team found that the temperature to which a tadpole was acclimated influenced the number of parasites that infected the tadpole, as well as the number of parasites the tadpole was able to clear. The experiment showed that tadpoles acclimated to moderate temperatures cleared more parasites than those acclimated to colder or warmer temperatures. These non-linear acclimation effects were most pronounced when tadpoles were exposed to parasites at cooler temperatures.

As part of the same project, collaborators at the University of Colorado at Boulder conducted a reciprocal experiment with the flatworms, acclimating them to varying temperatures to determine how shifting temperatures influenced their ability to infect tadpoles. Again, the parasites seemed to perform best when they were acclimated to moderate temperatures, but this effect was more pronounced at more extreme temperatures – very cold or very warm.

“Our results showed that both parasite temperature and host temperature matter when you’re trying to predict disease outcomes,” Altman said.

The team’s findings have been published in the “Journal of Animal Ecology,” a peer-reviewed journal of the British Ecological Society. Read the article here.

“I’m very grateful for the opportunity to do research like this,” Altman said. “This is my first publication, and I’m glad it’s going to be in a great journal that is widely read.”

Dr. Raffel emphasized the importance of this work, noting that few studies have demonstrated effects of temperature shifts on parasitism.

“This is the first study I know of to document thermal acclimation effects on a parasite’s ability to infect hosts,” Dr. Raffel said. “I think it’s likely to become an influential paper.”

He added, “Karie did an impressive job pulling together results from a complex and ambitious series of experiments, to tell a coherent and exciting story about the thermal biology of parasitism.”

To learn more about Oakland’s Department of Biological Sciences, visit Oakland.edu/biology.