‘Being the voice’

Study led by OUWB student highlights needs of polio survivors

An Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine study sheds light on what it’s like to be a polio survivor today — and highlights the need for physicians to be prepared to treat them.

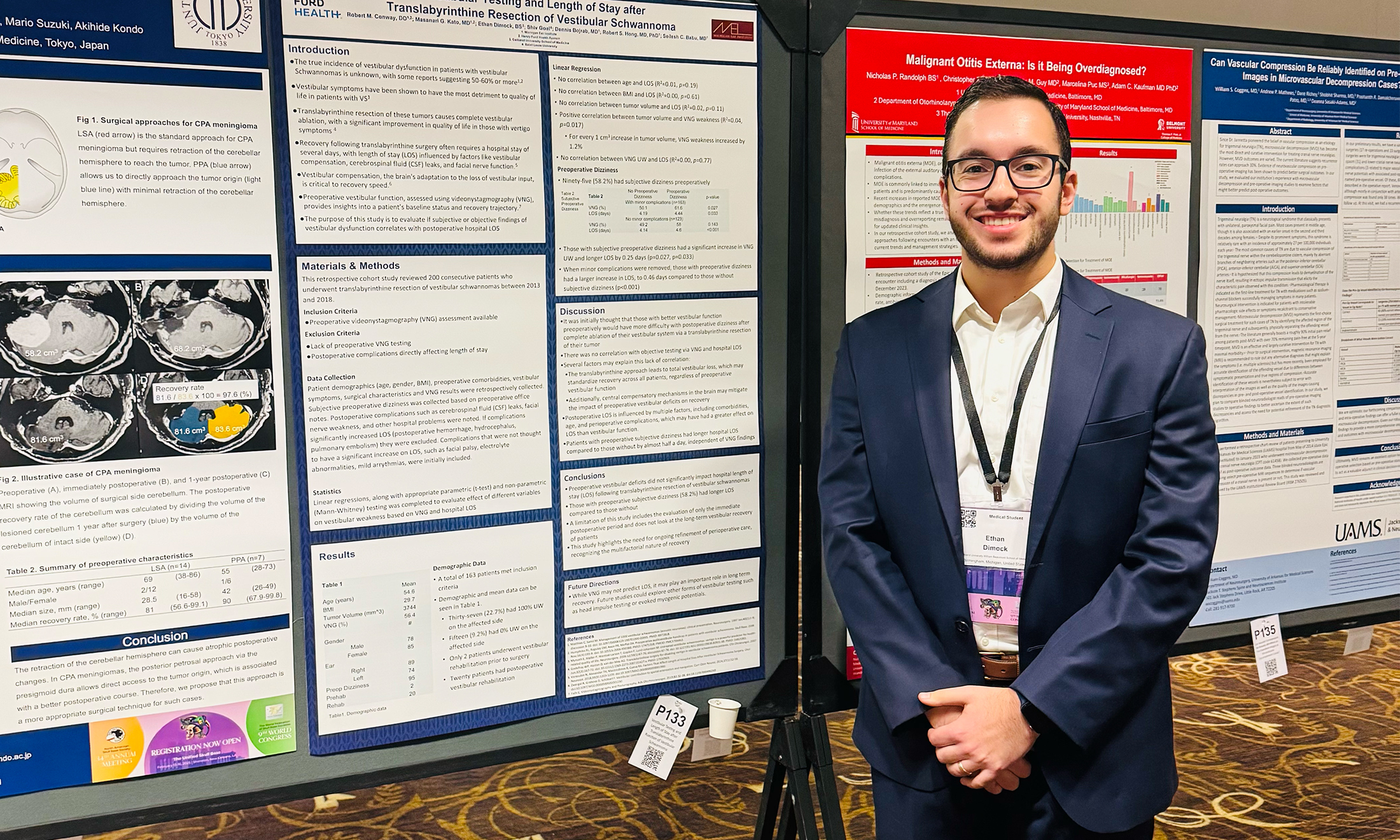

“Post-Polio Syndrome and Polio Survivor Biographies” was led by Amy Halder, a third-year medical student at OUWB. The poster was recognized as the best during OUWB’s 2021 Medical Education Week.

Believed to be first-of-a-kind research, the study explores the combination of the polio experience and condition known as post-polio syndrome, the major experiences that polio survivors share in terms of life history, and how they manage big disruptions in their lives.

The work was done in close conjunction with the Southeast Michigan Post-Polio Support Group.

“What inspired me was I wanted to be the vessel to allow the polio survivors to have their voices heard,” says Halder.

Tracey Taylor, Ph.D., associate professor, Department of Foundational Medical Studies is a co-author of the study. She says there isn’t a lot of money available for such research.

Among the key points of the study, she says, is that physicians aren’t always prepared to treat polio survivors. The study found that there have been instances where polio survivors have actually had to educate their physicians.

“Post-polio affects individuals who had polio as children, so it’s this little bubble population from before the vaccine was available who are now elderly,” she says. “There’s this perception out there that people shouldn’t learn about it because they won’t have to worry about it.”

‘A very educated group’

The association between representatives and the Southeast Michigan Post-Polio Support Group dates to the early 2010s.

Taylor connected with members of the group after one of the school’s “Lunch ‘n Learn” events held in 2014. The topic of the event was polio.

As a microbiologist — and having had taught about polio previously — Taylor says she was interested in keeping close ties with the organization.

Starting in 2015, Taylor made annual visits to talk with polio survivors about polio, though she notes “they know more than a virologist knows about polio virus.”

“They’re a very educated group,” she says. “And they’re just wonderful, wonderful people.”

Taylor says she always wanted to do something more with the group, too.

“I wanted to get involved with more community-based education and research,” says Taylor.

That’s when Halder entered the picture.

‘Being the voice’

Halder wanted to do a community-based research for her Embark project at OUWB. Specifically, she says, something related to polio.

Embark is a required scholarly concentration program of OUWB that provides a mentored introduction to research and scholarship. The four-year longitudinal curriculum consists of structured coursework in research design and implementation, compliance training, research communication, and scholarly presentation, with protected time to develop mentored projects in a wide-range of community and health-related settings.

According to the study, prior to the development of vaccines in 1954 and 1960, polio virus infected more than 55,000 children annually in the U.S., with about 21,000 of the infections leading to paralysis.

Up to 40 years post-recovery from a polio virus infection, many survivors suffer from post-polio syndrome, a new weakening in muscles that were previously affected by polio along with muscles that were not originally affected.

As the study notes, no other research could be found that explored the combination of polio experience and PPS, major experiences that polio survivors shared in terms of life history, and how they managed to deal with certain disruptions in their lives, such as being taken away from school and separated from family.

Halder and Taylor developed the idea for a project that would essentially allow members of the post-polio support group to “leave their mark.”

“Being the voice for a group of people that may not be able to speak up has always been sort of my underlying theme and really what drove me to medical school,” says Halder.

For the study, a mixed-methods approach was used to gather qualitative and quantitative data. Questions for surveys, focus groups, and one-on-one interviews were developed by Halder, Taylor, and additional co-authors Tracy Wunderlich-Barillas, Ph.D., director of Research Training, and Lucas Nelson, M4, OUWB.

Halder says respondents were excited and very eager to share their stories.

Several themes emerged, including isolation and loneliness, struggles to return to “normal life,” and stigma.

“Even long after we had polio and we were, you know, fine, people said ‘Oh kids can’t come play at your house because that’s a polio house,’” states one response in the study.

Yet, other themes were related to determination, perseverance, optimism, and the importance of support from others.

“When asked the titles of their hypothetical autobiographies, one participant responded with ‘Polio as a Springboard, Not a Dead-End Street’ because “my life would not have been as rich and full without polio,” states the study.

The study concludes that physicians should be aware that polio had major implications in the lives of polio survivors. Further, the study states that support plays a big role in health outcomes of patients living with chronic conditions.

“The long-term goal is to illuminate physicians and society about caring for polio survivors as well as individuals living with other chronic illness/disease physicians may not be always familiar with,” says the study. “Regardless of a patient’s condition, it is important to have good listening skills and patients tend to remember those physicians who are willing to educate themselves and learn from patients.”

Halder says her big takeaway from the project is the importance of listening.

“It’s basically what we are taught in medical school — listen to your patients, have an active, open mind to learn, and don’t think you know it all,” she says.

March 22, 2022

March 22, 2022

By Andrew Dietderich

By Andrew Dietderich