‘Suddenly, I couldn’t walk’

OUWB medical student shares story to raise awareness of rare disease

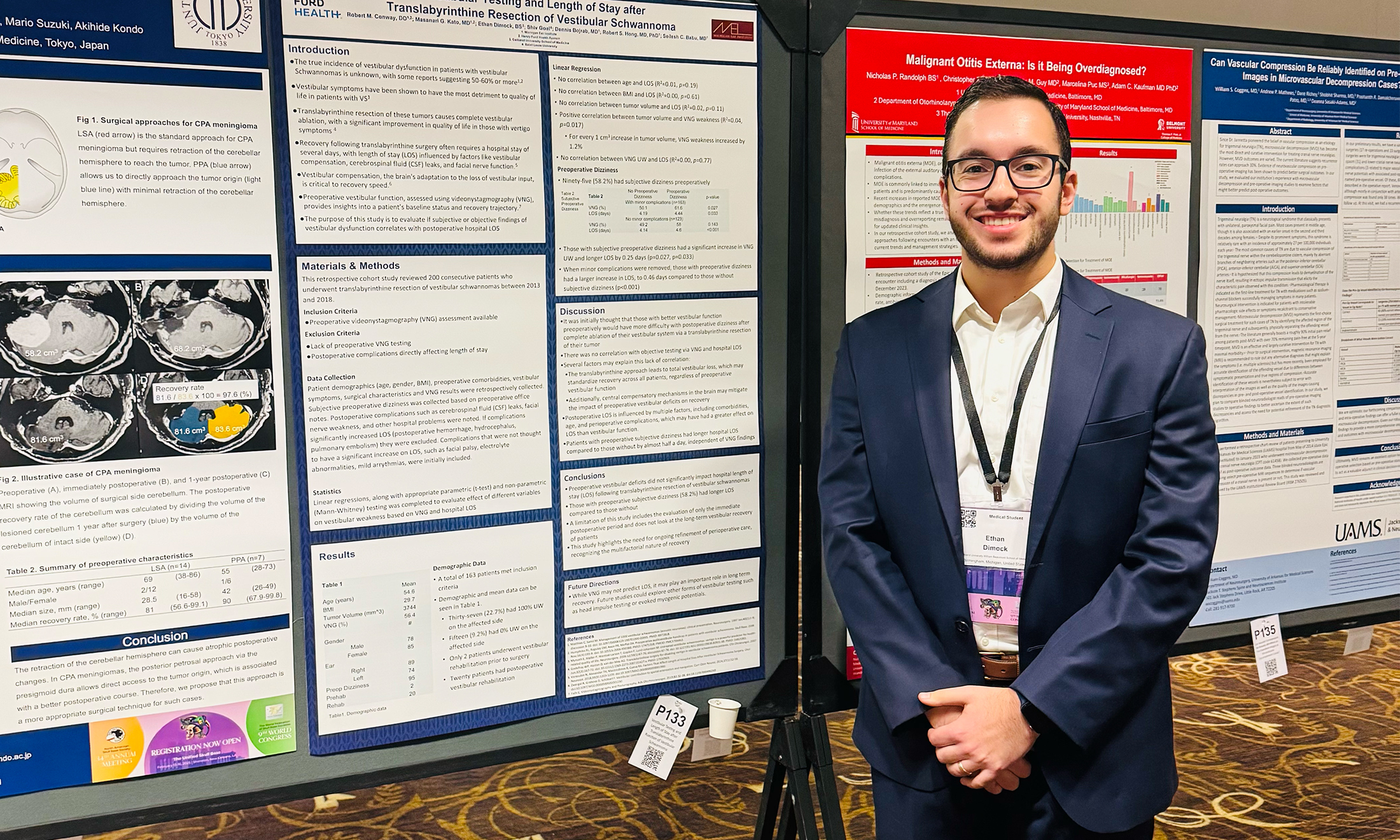

Fortune brought Jessica Cummings and Andrew Eibling together at OUWB, where each expected to become a doctor — but neither could have anticipated the unique and challenging journey they would face.

Unique because neither expected to fall in love with another person within weeks of starting medical school.

Challenging because neither expected Jessica would develop a rare and painful condition that would force the couple to travel around the country for treatment and take a year off from medical school.

Unique because of the way the OUWB community would lend support, both in spirit and financially.

And challenging because of the lessons they would learn about health care — the kind of lessons that can’t be learned from a book or lecture.

The kind of lessons Jessica hopes others can take away from her story.

“I was apprehensive about sharing my story because it’s so personal, and bringing a stigma upon yourself is hard,” says Jessica. “But I want to bring awareness to a rare disease and what patients with rare diseases experience.”

“I also want to break the stigma around chronic pain,” she adds. “Because I’m not lazy. I don’t just want pain medication. I want nothing more than to leave this behind me forever.”

‘Super pretentious about vitamin D’

Jessica and Andrew did not know each other when they each began their medical school journey at OUWB in 2021.

Andrew came from Colorado, where he earned an undergraduate from Colorado State University.

Jessica grew up in metro Detroit. She earned an undergraduate degree from University of Michigan.

Jessica’s parents — both physical therapists — met at the anatomy lab OUWB shares with the OU Physical Therapy program. That’s also where Jessica and Andrew ended up being lab partners.

By November 2021, they were dating.

“I liked her sense of humor,” says Andrew. “It’s awesome when your friends want to hang out on a Friday afternoon and you can say ‘I actually just want to hang out with this person because they’re fun.’”

Andrew also says he “loved her fight, from day one.”

“She always fights for those considered to be down and out…people who don’t necessarily have a voice for themselves,” he says.

Jessica agrees they “clicked really well,” and that they could find joy in the most mundane of tasks.

“Another thing I really liked about Andrew was his positivity,” says Jessica. “Medical school is hard and stressful, but he always had this spin on it that he was really just fortunate to be able to be here and learning this information that was so cool.”

The couple also enjoyed outdoor activities. Andrew calls them “super pretentious about vitamin D,” referencing a shared love for the sun.

But after doing so during one long run, Jessica suddenly felt something was wrong, seemingly out of nowhere.

‘I was just scared’

Jessica had been a distance runner her whole life, and “that wasn’t going to change during school.”

One day, however — in early 2022 — she didn’t have a choice.

“We just took the cardio final and I ran 17 miles in training, and I just felt a little off and didn’t know why,” she says.

Nothing out of the ordinary had occurred — she didn’t fall, step weirdly on anything, over extend, fracture, etc. She simply had an inexplicable “light throb” around her left foot.

“I decided to take time off from running and with rest, it continued to worsen,” she says.

The affected region got to a point of being so sensitive, says Jessica, that touching it with a feather “would feel like a blowtorch” against her skin.

“I didn’t know it was possible to experience that much pain,” says Jessica.

The affected area also would become extremely cold and turn a dark, deep red, almost purple.

“I started having trouble walking and suddenly, I couldn’t walk,” she says.

In the beginning, answers were non-existent — and that made things worse.

“I was just scared,” says Jessica. “I didn’t know what was happening. Nobody, even doctors, could tell me what was happening.”

Andrew couldn’t feel Jessica’s physical pain, of course, but he hurt, too.

“I cannot describe the pain a person feels when a loved one is in pain,” he says. “Whether it’s emotional or physical…it’s just really spooky, and made me feel an immense sense of gravity about the situation.”

‘I didn’t know if I would ever walk again’

Shortly after the couple finished their first year at OUWB, it was a podiatrist that finally diagnosed Jessica with Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy (RSD), which is also called Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS).

It’s a condition that is rare, and not very well understood. It isn’t genetic. It’s believed to be the result of a dysfunction in the central or peripheral nervous system. In short, the abnormal functioning results in an overreaction to pain signals that the nervous system can’t shut off.

“I just remember being at that appointment and feeling shocked because it wasn’t a statement like ‘You broke your ankle,’” says Jessica.

The doctor told Jessica that treatment for CRPS could take years.

“I was hyperventilating and almost passed out,” she says. “I didn’t know if I would ever walk again.”

In hindsight, Jessica says she feels fortunate that her CRPS was diagnosed in less than two months from symptom onset — it takes nine months for the average CRPS patient.

Still, the diagnosis came two weeks before Jessica and Andrew had plans to go to Europe as part of the OUWB group that participated in the school’s inaugural study trip to Auschwitz (part of its Holocaust and Medicine program).

During the June 2022 trip, Jessica used a knee scooter or crutches to get around Poland. They told others she had broken her foot.

“It was so hard for me to talk about it at that point,” she says. “Also, being in significant physical pain — and emotional pain for that matter — the whole time we were there…it was just so hard.”

Upon return to the U.S., she essentially began the long road to recovery.

Though medications can be effective in treatment of CRPS, they didn’t work for Jessica. Other treatments included biofeedback, motor imagery, mirror therapy, pain psychology, and nerve blocks.

The mainstay of treatment, according to Jessica, is physical therapy — but it’s a long, slow process.

‘The kind of doctor I’m going to be’

Jessica and Andrew began their second year of medical school, but it was too challenging.

“I’d be sitting in class and a sock would feel like nails piercing into my foot,” she says. “People are talking about the kidney or something and you’re just trying to slowly breathe because you’re in so much pain you can’t focus. I had to come to terms with the fact that I couldn’t be in school yet.”

Andrew made the decision to take a leave, as well.

“It comes down to priorities,” he says. “Do you value finishing school one or two years sooner, or do you value having the love of your life walk? If you put it that way, it’s a pretty clear distinction.”

“I couldn’t care less about what residency programs or anything like that think about the decision we made because we made the right one,” he adds.

For now, both are working as clinical research coordinators at University of Michigan.

That keeps them connected to health care, and affords the flexibility of working from home.

They travel often as the different specialists Jessica needs are located throughout the U.S.

The hope is to return to OUWB for its next school year, but its uncertain if Jessica will make enough progress in physical therapy by that time. She says currently, the condition is “improving.”

One thing that is certain, however, is that Jessica has an abundance of support that seems unwavering — starting with Andrew, her now fiancé.

Jessica says she “never felt he was trying to prioritize anything else over the situation that I was facing.”

“He just stood strong and was like ‘This is absolutely what matters and I’m not going to think twice about it,’” says Jessica.

‘Invaluable feeling of support’ from OUWB

The OUWB community also stepped up to support Jessica and Andrew. OUWB M2 Jessica Krone started a GoFundMe fundraiser for the two. So far, more than $9,000 has been raised.

Krone says she started the fundraiser because Jessica and Andrew’s situation left her at a loss for words and she found herself thinking about their situation a lot.

“Jess is a young, active, medical student just like I am, so the thought that this is happening to someone just like me really stayed in my mind and motivated me to find something to do that would bring any sort of benefit to her situation,” says Krone. “They are phenomenal people with big hearts, and I was happy to do anything to help them through this challenging time.”

Monies raised will be used to cover costs associated with Jessica’s ongoing treatment.

The couple is thankful and shocked by the response.

“There is a lot of power in a supportive community that drives someone towards healing,” she says. “Andrew and I were completely blown away…the OUWB community rallied around us and gave us a huge gift and not just a monetary one…also the invaluable feeling of support.”

It’s the kind of support that is helping Jessica make progress in her treatment as the couple looks ahead with excitement.

“We’re still very focused on my recovery because we’re not where we want to be and we continue to be told that I can still get better from here,” says Jessica. “But we also know that we are going to be doctors someday…whether that happens starting this year or next year, that’s our plan and dream for the future.”

And when it does happen, both point to a certain kind of enlightenment that comes with healing from a traumatic experience — and will make them better physicians.

“As a doctor, you may only see a handful of rare diseases in your entire lifetime, but those handful of patients have lives, and people who love them,” says Andrew. “It’s shown me the importance of being observant and compassionate, and to respond in a timely manner…there have been doctors that have left us hanging for months.”

Jessica realizes that now, even more than ever, she wants to be a doctor. Among other things, so she can bring awareness to how long it takes some patients to even get a diagnosis.

“This experience has lit a fire under me to become a compassionate doctor who truly listens to patients and refuses to give up on them,” she says. “If I had heard there was a doctor somewhere that truly understood what it was like to live with a rare disease and was not going to give up on me, I would have been right there.”

“That’s the kind of doctor I’m going to be.”

April 27, 2023

April 27, 2023

By Andrew Dietderich

By Andrew Dietderich