Knowledge gap

Sixth Annual Krug Lecture in Biomedical Ethics at OUWB takes on epistemic injustices

The gap between how people with disabilities describe the character and quality of their experiences and how clinicians view those same things was the topic of an OUWB event last fall.

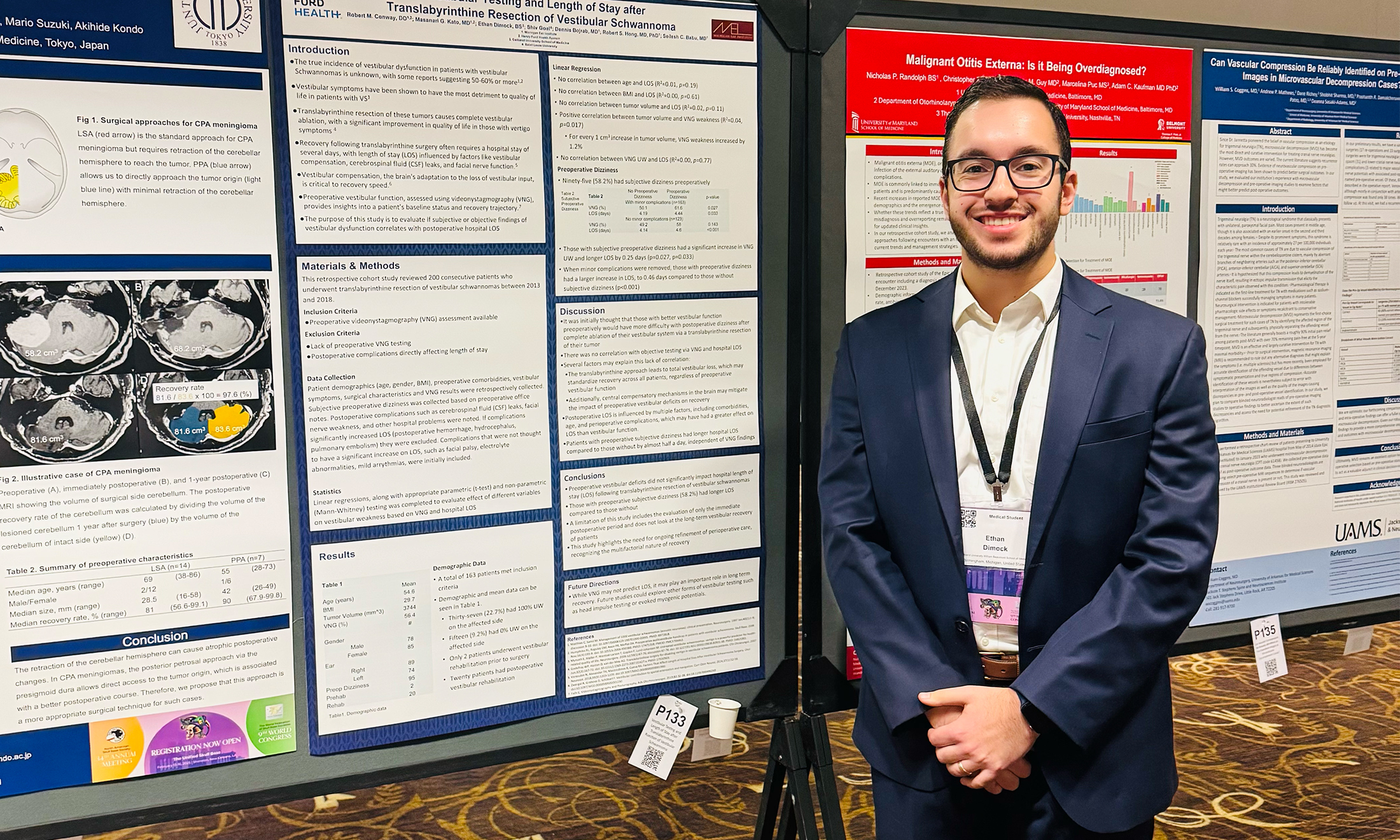

More than 50 people attended the 6th Annual Ernest and Sarah Krug Lecture in Biomedical Ethics held online and in person at the Auburn Hills Marriott Pontiac.

The featured speaker was Joel Reynolds, Ph.D., assistant professor of philosophy and disability studies at Georgetown University, a senior research scholar in the Kennedy Institute of Ethics, core faculty in the disability studies program at Georgetown, and a senior advisor to the Hastings Center.

“Epistemic (In)justice in Clinical Practice: Where We Are and Where to Go” was the title of his presentation.

“This event series is fantastic, and I’ve been very impressed by OUWB’s commitment to bioethics, humanities, and thinking about medicine as both an art and science,” said Reynolds after his talk. “It’s an honor to be here.”

Jason Wasserman, Ph.D., professor, Department of Foundational Medical Studies, coordinated the event and noted the timeliness of the topic because “there’s a real surge across the country to address the complexity of disability and ethics.” Reynolds noted that one in five people are disabled, and if people live long enough, “all of us will be become disabled.”

“It’s a profound vulnerability and there’s quite a bit of injustice levied on people with disabilities,” said Wasserman. “It’s a topic that’s wide in scope and deep in significance.”

Wasserman also talked about what he hoped attendees would take away from the presentation.

“Most of the people (at the Krug lecture) are sympathetic to the need to create a more just and accessible world for people with disabilities,” he said.

“But what the speaker brought to the table that people maybe haven’t thought as much about is the notion of epistemic injustice and meaning.”

‘A knowledge gap’

Reynolds started by sharing stories involving patients marginalized and oppressed.

One, as featured on NPR, was of a patient with an intellectual disability who was taken to the hospital with COVID-19. A doctor in the small Oregon town denied her the ventilator she needed, citing a “low quality of life.” Eventually, she was moved to another hospital where she did receive the care she needed – but not before a large legal battle.

Reynolds also referenced “Trisomy 13 and 18 – Treatment Decisions in a Stable Gray Zone,” an editorial written by John Lantos, M.D., and published in JAMA. The editorial explains how pediatric residents once were taught that trisomy 13 and 18 should be considered lethal congenital anomalies, and that parents should be told these conditions were incompatible with life.

It turned out, however, that assumption is wrong in many cases and survival is not as rare as once thought. Reynolds used it as an example of how preconceived notions can essentially lead to self-fulfilling prophecies.

With those stories establishing the tone of his talk, Reynolds identified the following as his primary takeaway:

“There is often a knowledge gap between how people describe the character and quality of their own experiences vs. how those experiences are understood by clinicians.”

It’s a discrepancy, he said, that can lead to medical errors.

The reason, he added, is because of epistemic schemas linked to group- or identity-based biases rooted in categories like race, sex, and/or disability.

Reynolds defined epistemic schemas as “the framework in which not only things are known, the framework in which people are judged to be knowers whether experts or not, the framework in which things are judged to be knowable, and the framework in which specific claims can be true or false.”

Epistemic schemas are especially recalcitrant, he added.

“It is much easier to change a particular piece of knowledge that one has — to learn things or take away from what one knows — than it is to identify much less change the entire framework in which one knows,” he said.

This all leads to epistemic injustices, said Reynolds.

Epistemic injustice “refers to the ways in which someone can be wrong as a knower…as a knowing, reasoning, questioning being.”

Reynolds further identified two types of epistemic injustice: testimonial injustice and hermeneutical injustice, aka interpretive injustice.

Testimonial injustice is where someone’s testimony is downgraded, perhaps to the point of not believing the person at all, based on a particular prejudice against the individual. By example, he noted the “sad, well-known” belief by “a significant percentage of physicians” that Black people have higher levels of tolerance for pain.

Hermeneutical injustice occurs when a person is rendered unable to understand and/or articulate important aspects of their experiences because there are “no tools to think about it.” An example Reynolds used was postpartum depression — specifically, how it was dealt with before it was recognized as a condition.

By creating awareness of such injustices, however, Reynolds said health care can improve.

“Epistemic injustices are everywhere around us, all the time,” he said. “By paying attention to them, we usually can figure out how to do things better and treat people better.”

In conclusion, Reynolds offered three tips for how to avoid perpetrating epistemic injustices:

- Fuse clinical understandings with patients’ lived experiences.

- Share authority in communication and decision making.

- Elevate patients as experts in living with disabilities.

“I hope that clinicians feel more confident in their ability to provide equitable quality of care to their disabled patients,” said Reynolds after his presentation. “I also hope that clinicians have a more complex understanding of how frameworks of knowing can both contribute to, but also sometimes get in the way of providing the best care.”

An ‘inherently important’ topic

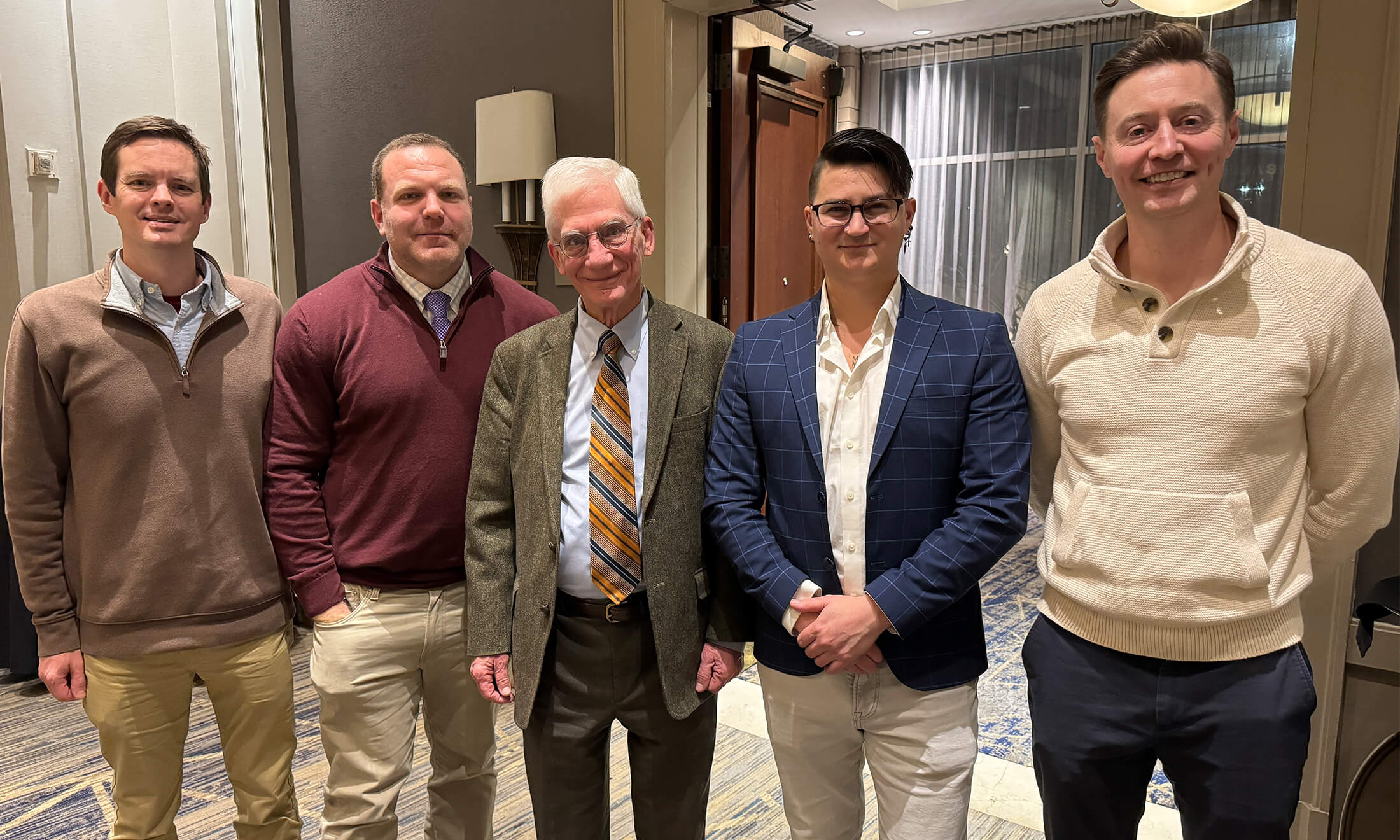

Before retirement, Ernest F. Krug III, M.Div, M.D., served as Beaumont’s (now Corewell) director of the Center for Human Development and established Beaumont's first clinical ethics consultation service. After joining the inaugural faculty at OUWB, he developed the Medical Humanities and Clinical Bioethics (MHCB) longitudinal curriculum.

The Krug Lecture in Biomedical Ethics is made possible by a generous donation from Ernest Krug and his wife, Sarah Krug. He attended this year’s lecture and called it a “great presentation.”

“It’s such an important topic because we really need to have an attitude of respecting diversity in our society,” said Krug. “We need to be careful not to marginalize people…not to see certain people as the normal people and these other people are not normal. (Reynolds) put that very succinctly in his talk.”

Among the attendees was Ven. Kevin Hickey, who manages a group of eight chaplains at Corewell Health William Beaumont University Hospital in Royal Oak, and is an instructor at OUWB, where he teaches MHCB seminars.

“The topic and conversation around disability is inherently important in the world that we live in for the reasons that Dr. Reynolds identified,” said Hickey. “It’s good to hear perspectives from an expert in the field so that we can think about these dilemmas and phenomena in more expansive ways.

M1 Diana Mansour attended and said she’s always looking for opportunities to learn how to one day be the best doctor she can be.

“For a patient to see a doctor puts them in a really vulnerable state so it’s important for us as physicians to learn how to understand our patients and hear them so that we can build a better relationship with them,” she said. “And having a strong relationship with your patients is probably the most important thing.”

“Discussions like this…can help us serve our communities and patients better,” she added.

February 01, 2024

February 01, 2024

By Andrew Dietderich

By Andrew Dietderich