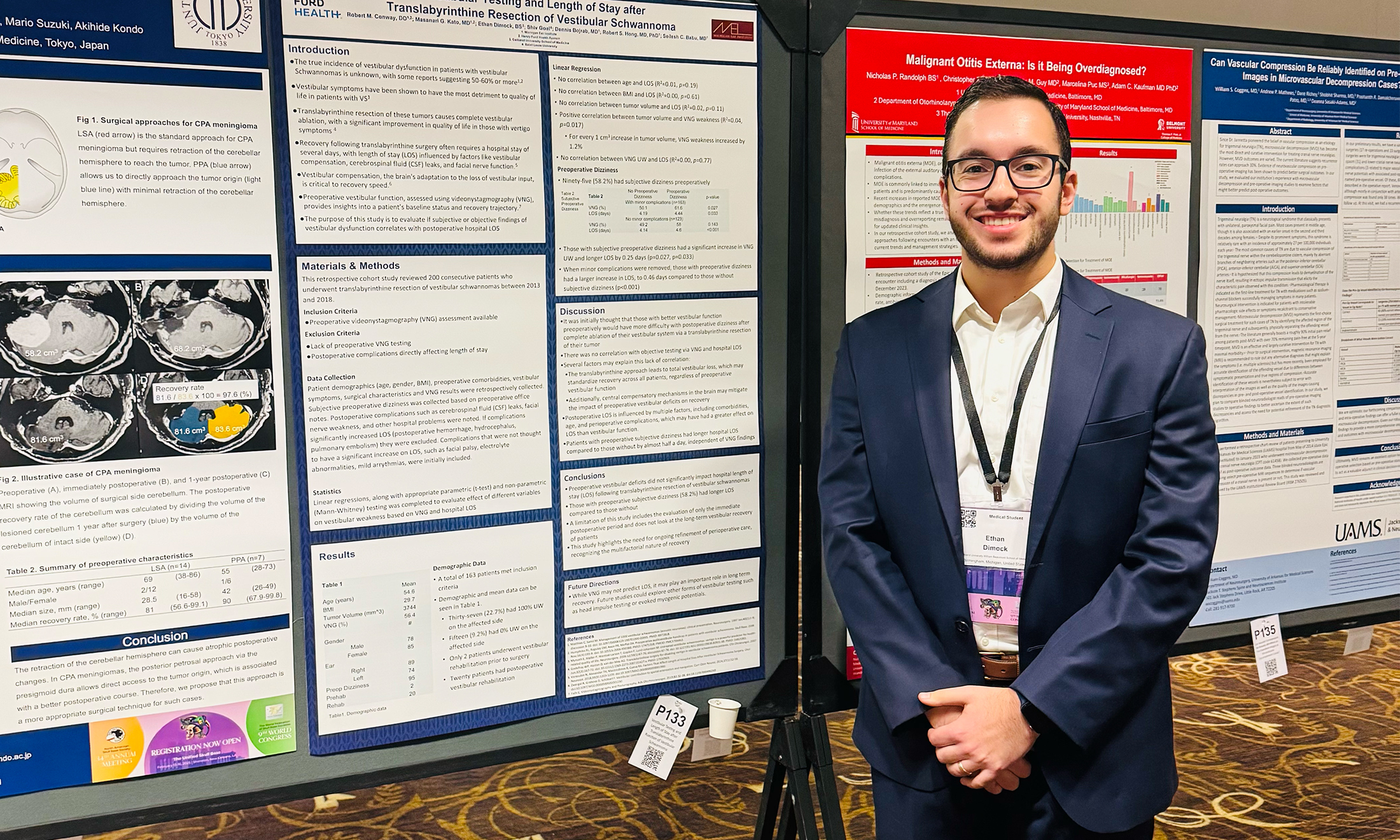

Olympian, M.D.?

OUWB’s Skyler Porcaro eyes 2024 summer games while coaching OU track team

An OUWB student is coaching Oakland University’s javelin throwers — and hasn’t ruled out making his own run for the 2024 Summer Olympics.

The reason is simple: Skyler Porcaro, a third-year medical student, simply loves the sport and everything it affords him as a medical student.

That includes time away from studying, the positive physical and mental aspects of training and competition, and the drive to continually best one’s personal record.

Currently a coach for Oakland University’s javelin throwers, Porcaro says he hasn’t abandoned plans to be in Paris for the next summer games.

And even if he doesn’t make it, Porcaro says successfully balancing participation in sport at a high level with his studies will help him become a better doctor in just a few years.

“It taught me that I can be a good doctor and I can help my patients, but that I can also have hobbies and continue my education outside of medicine,” he says.

“Medicine is part of who I am, but it’s not the only thing I am.”

‘Doctors told me I wouldn’t play sports’

Porcaro was born in Utah, and at age two, doctors diagnosed him with Legg-Calve-Perthes disease, a hip condition.

“Doctors told me I wouldn’t play sports,” he says. “They said I wouldn’t grow to be as tall as I am and all of this other stuff.”

Sports like football and baseball helped him cope, he says.

When he was about to start 10th grade in high school, Porcaro participated in a softball-throwing competition. He ended up throwing it from goalpost to goalpost.

“They pulled me from baseball and said, ‘You’re going to throw javelin now,’” he says. “At the time, I had no clue what it even was.”

The javelin throw is a track and field event. Essentially, the javelin is a spear that’s just over eight feet in length. Throwers run in a predetermined area to gain momentum immediately prior to throwing the javelin as far as they can. The men’s gold medal winner at the 2020 Beijing games threw 87.58 meters.

Almost as he began throwing, Porcaro found success in javelin. He was not only a natural thrower, he says, but he also quickly learned to love what he calls the meditative aspects of the sport combined with the need to continually push oneself towards improvement.

“Sure, you are competing against other people, but at the end of the day you’re competing against yourself — you get your personal best and the goal is just to do whatever you can to improve on that. I didn’t ever really get that in other sports.”

Porcaro racked up records at local, regional, and state levels, competed in national meets, and gained attention from college coaches. He spent two years after high school on a church mission before he picked up where he left off as a javelin thrower at Southern Utah University.

As he did in high school, Porcaro pushed himself towards success — it didn’t take him long to break the school’s javelin throw record. But in his second season, he tore a ligament in his elbow, and had to have Tommy John surgery.

Still, quitting was never an option.

Porcaro rehabbed and in his senior year, competed in the 2019 Toyota USATF National Championships and finished as the 16th best javelin thrower in the U.S. He qualified for the 2020 Olympic trials.

While training at OU for the trials (eventually delayed a year due to COVID), Porcaro ran into the school’s track coach who expressed interest in having him help the team’s javelin throwers. He agreed and has been doing it since.

In early 2021, Porcaro married his wife, Lacey. The couple met at Southern Utah and were teammates in track and field. Lacey also helps coach OU’s track team.

Also in early 2021, however, Porcaro reinjured his arm and his hopes for the 2021 games were over.

Still, they remain in place for the next Olympics.

“I’m rehabbing right now and planning to get back into training and throwing this year, but more so for next year,” he says. “It’s a long recovery on the injury.”

If everything goes as planned, Porcaro will be in prime shape for competition after his Match Day in 2023. That's exactly when the the Olympic trials will be held for 2024.

Porcaro’s hopeful his residency will be flexible should his Olympic ambitions pan out.

Should he get injured a third time, says Porcaro, he’ll have to look at “maybe stopping.”

‘Medicine is…not the only thing I am’

Porcaro says his interests always have varied and balanced. In addition to playing football and being part of the track team, he played cello in the orchestra and took calculus classes.

“I’ve had a lot of friends and peers in the different parts of my life with different desires and goals,” he says. “That taught me that balance is something that I want in my life.”

It’s an approach that helped him earn undergraduate degrees in biology and Spanish while preparing to apply for medical school. Porcaro says it’s also helped him balance studying at OUWB with his outside interests.

Currently, Porcaro is planning to apply for residency in physical medicine and rehabilitation.

“I came to this realization that — with my hip and background in sports — the reason I wanted to go into medicine was the continual care of chronic pain and rehabilitation,” he says.

“As soon as that clicked it provided a clarity that I’ve been able to carry through third-year…I’m able to pull stuff out of every rotation that is relevant to what I want to do.”

Wherever Porcaro ends up, he says he firmly believes his experience as a javelin competitor and coach will help him be a better physician.

“Javelin has taught me to look at myself and how I can improve,” he says. “It’s also taught me to find the joys and rewards in the achievements of others.”

March 22, 2022

March 22, 2022

By Andrew Dietderich

By Andrew Dietderich