‘The challenge was worth it’

OUWB alum Chris Jaeger, M.D., ’15, delivers message to Class of 2022

OUWB alum Chris Jaeger fully expected to be an engineer until one conversation changed the trajectory of his career and lead him to become a doctor.

The person was Ken Peters, M.D., Peter & Florine Ministrelli Distinguished Chair in Urology, OUWB.

The conversation?

“He was a family friend…and very invested in mentorship,” says Jaeger, ‘15. “He convinced me to strongly consider medicine, and I did.”

As a result, Jaeger went on to graduate from OUWB’s inaugural class, became OUWB’s first urology match, spent five years as an intern and resident at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, and currently is a pediatric urology fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital.

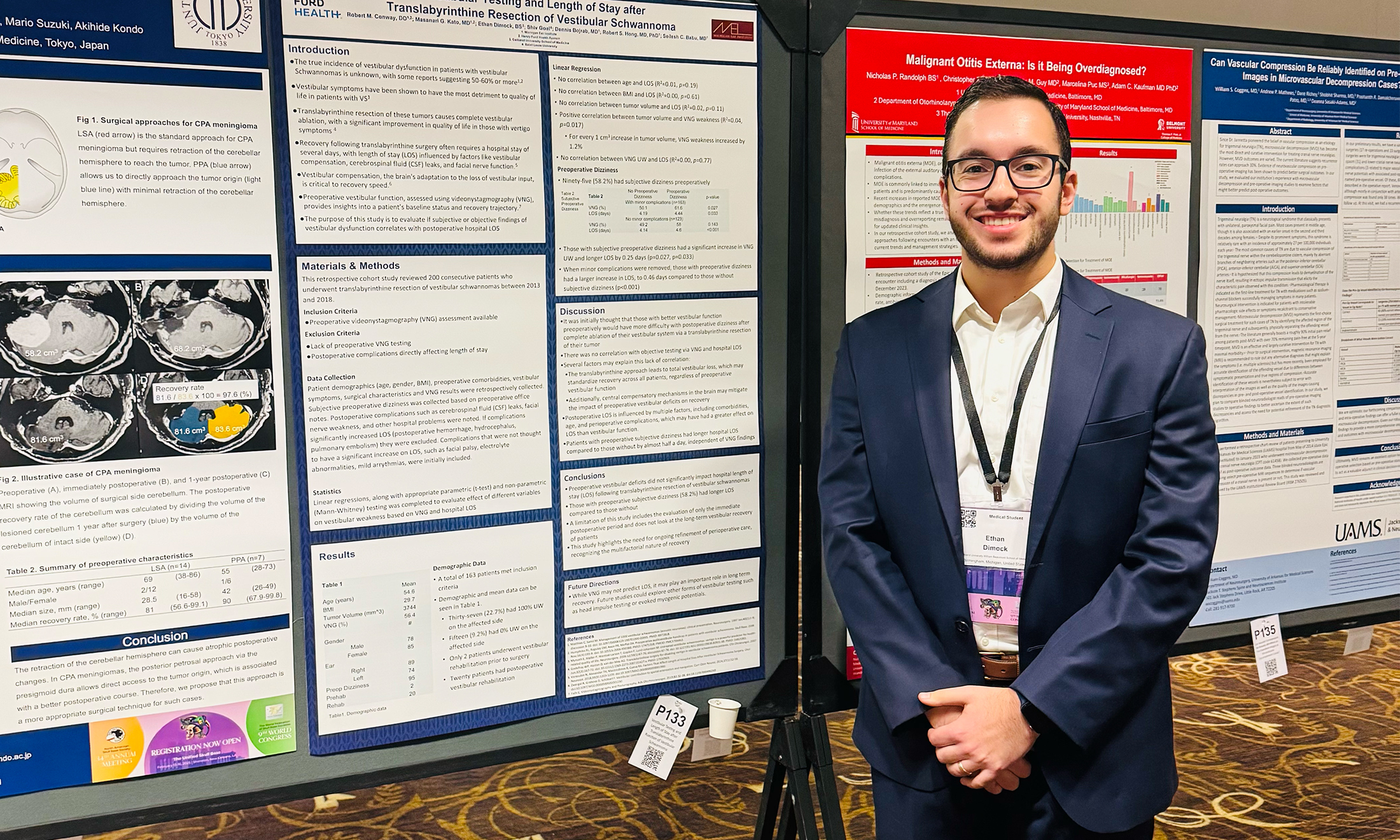

Amidst a busy schedule, Jaeger took time off in May to return to OUWB as the alumni speaker at the Class of 2022 commencement.

“You will grow to become experts in your fields of study,” he said. “You will discover new and better ways to deliver high-quality, compassionate patient care. I expect that many of you will invent new therapeutics, surgical procedures, care pathways, and teaching methods to ready the next generation of doctors in training.”

“Simply put, you all will do great things,” he said. “I know this because you are graduating from OUWB.”

‘Patients were so thankful’

Jaeger grew up in Royal Oak, where he attended Royal Oak Shrine High School — located directly across the street from Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak.

He went on to attend University of Michigan, where he was on track to become an engineer. About halfway through the program, however, he had the conversation with Peters.

“He painted a picture where one could be on the cutting edge of technology and medicine, which is where I was as an engineer, but could also be patient-facing at the exact same time within the exact same profession — and he modeled that by showing me the operations that he does,” says Jaeger.

Specifically, he says, Peters showed Jaeger an operation called percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation — an FDA-approved process that involves inserting an electrical lead to help control overactive bladder.

“It’s a last-ditch effort that works for a shocking number of people,” he says. “And the patients were so thankful...that’s really all I needed to see in order to be convinced that medicine was the right thing for me.”

During his junior year at Michigan, Jaeger was among a small cohort to participate in a pilot for what would become OUWB’s team-based learning approach to medical education.

A little more than a year later, he would be one of 50 in OUWB’s inaugural class.

‘I needed to be here’

Jaeger says it doesn’t matter how many other offers he received for medical school because when it came to OUWB, “I needed to be here.”

The biggest reason, he says, was OUWB Founding Dean Robert Folberg, M.D.

“He was able to tell a story as to how he saw medicine transforming in the next five to 10 years, and the need that (OUWB) was addressing,” says Jaeger. “As an impressionable young person wanting to enter the field and be like some of his mentors, it was a no-brainer.”

Jaeger says being part of school’s first class was “extraordinary,” and that he and his Class of 2015 classmates continue to care deeply about OUWB and each other.

“That group was very close…as close as any class will ever be,” he says. “One, we were a small class, and two, we were in solidarity battling through some of the highs and lows.”

He generally describes the lows as “growing pains” that any new school might experience, but says they only really meant opportunity for growth.

“We were allowed to create, (and) given permission to be part of the future of OUWB,” says Jaeger. “Partly because we were the charter class, but also because of the infrastructure that was set up by Dean Folberg.”

When the Class of 2015 graduated, Jaeger says “it was an emotional day.”

“Everybody, and not just the students, was ecstatic that we had gotten to that point,” he says. “When you get to commencement, you look back on all of the things that you’ve accomplished during medical school and I think a lot of people are very emotional.”

When he started residency at Ohio State, Jaeger says he “felt very prepared.”

“As far as competency and the stresses of talking to patients about difficult things, shared decision-making, breaking bad news…these are things that cause trainees immense stress and a lot of them don’t do it well in the beginning,” he says. “I felt very comfortable doing those things (because) OUWB teaches that very well…you can’t skip over, make light of, or not pay close attention to patients when they’re in vulnerable states.”

‘The challenge was worth it’

Today, when not working, Jaeger enjoys spending time outdoors with his wife, Kat, as they hike various trails on the East Coast and occasionally in U.S. National Parks.

He is winding down his fellowship at Boston Children’s Hospital, making plans for the next step in his career.

OUWB remains influential in his life.

“I was so inspired by how the OUWB medical educators treated me that I have devoted my future academic career to medical education, and I don’t think that’s uncommon,” he said. “Being part of the charter class really influenced my life in more ways than one. It prepared me for the clinical side of things, but it also made me feel indebted to those who taught me and empowered to be one of them.”

Being invited to speak at the Class of 2022 commencement represents one of the ways Jaeger says he wants to give back to OUWB. In congratulating the graduates, Jaeger says his primary goal was to capture the voices of the classmates he once sat with as newly minted physicians.

He also reflected on advice given Mary Fisher, an AIDS activist who received an honorary Doctor of Humanities degree and delivered the Class of 2015 address.

“Mary challenged us to have the courage to be intimate and the nobility to be vulnerable with our patients,” he said to the class. “She encouraged us to have a soul and she dared us to love our patients. She tasked us with these challenges because she knew that in such humanitarian acts there is healing beyond science and words.”

Jaeger noted that, in practice, this can mean: being an advocate for the vulnerable; hugging a patient in despair after a cancer diagnosis; spending a few extra minutes on trauma call to comfort a concerned family member; and/or playing with a pediatric patient in the hospital who just wants to feel like a kid.

“These actions are not in the guidelines, but they may be the most important things you can do for your patients, and yourself in practice,” he said. “I urge you to remember that the practice of human medicine is inseparable from the practice of human grace. This principle is fundamental to the humanistic mission of this school and has inspired me to choose empathy over indifference.”

“When I heed this advice, I remember why I went into medicine and why the challenge was worth it,” he said.

July 06, 2022

July 06, 2022

By Andrew Dietderich

By Andrew Dietderich