From Ancient Genes to Modern Machines

Decoding ancient microbial evolution to engineer modern solutions, Dr. Fabia Ursula Battistuzzi uses molecular data and computational tools to trace disease origins and tackle environmental challenges.

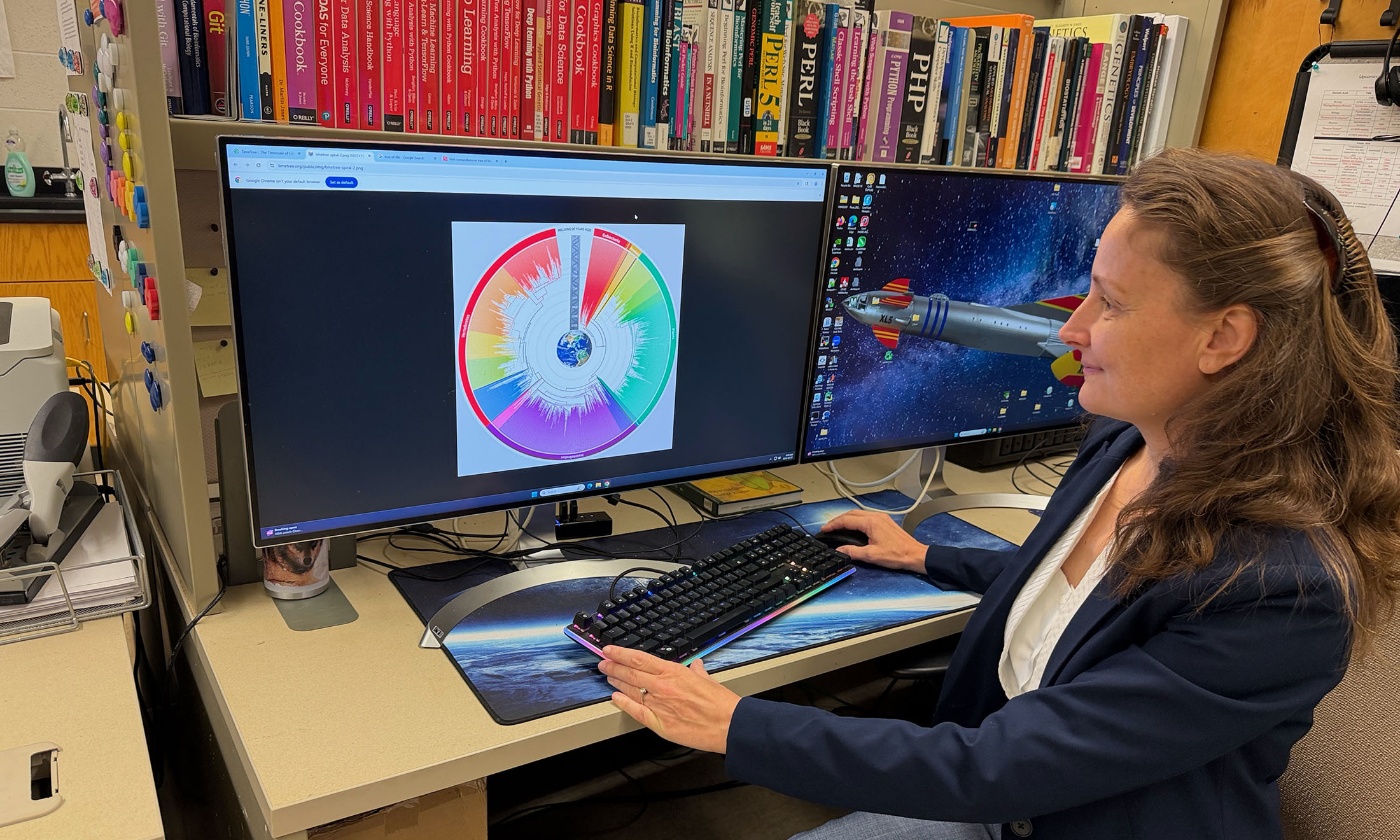

Life is born not merely in cells, but in stories of adaptation and transformation. In this story, Fabia Ursula Battistuzzi, Ph.D., professor of bioengineering and biological sciences, stands at the crossroads of ancient microbial evolution and modern bioengineering. For over two decades, she has been navigating molecular data and developing computational tools to understand how species evolve and how their genetic advancements drive biological functions, with applications ranging from tracing disease-causing microbes to engineering solutions for environmental challenges.

“There is a growing demand for research that decodes microbial functions and evolution because microbes play key roles in ecosystems and human well-being. Understanding genetic adaptations of pathogens, for instance, is crucial for tracking infectious diseases as it reveals how pathogens evolve and spread. It also supports the development of sustainable biotechnologies by harnessing microbial functions for various environmental applications,” says Dr. Battistuzzi, while describing her interest in creating predictive tools that connect evolutionary history to real-world solutions.

One cornerstone of her contributions is the development and application of new computational tools. To estimate the evolutionary timetrees of large prokaryotic phylogenetic trees, for instance, she helped create a new molecular clock tool, RelTime, which is now widely used. She also developed a protocol for application of Roary, a powerful bioinformatics tool that enables rapid and large-scale analysis of bacterial pangenomes –– a new paradigm that moves beyond single reference genomes by identifying genes shared across all strains: the core genome and the accessory genomes. This approach allows Dr. Battistuzzi and her team to explore the correlations between microbial adaptations and pathogenicity and clarify the genetic origins of infectious diseases.

“Looking at the evolution of malaria, for instance, we found that the origin of the agents of this disease –– Plasmodium –– in mammals is millions of years older than previously estimated. This means that models of rapid evolutionary adaptations should be revisited. This work provides a foundation to anticipate how pathogens may emerge or evolve, giving medicine and ecology critical predictive power,” she says.

An opportunity to push the frontier of bioinformatics and bioengineering even further arrived with the recent surge of machine learning and artificial intelligence capable of managing large databases. By integrating the powers of deep learning with a multi-omics approach, Dr. Battistuzzi could construct models capable of predicting gene functions that no human had ever experimentally tested before, while also training OU graduate students in advanced data science.

As a principal investigator on the National Science Foundation Research Traineeship grant, she integrated big data analytics, bioinformatics and machine learning to enable students across biology, bioengineering, statistics, computer science and business fields to handle large-scale biological datasets. The grant also supports projects like the multi-omics machine learning model to identify unknown gene functions related to plastic biodegradation and other biological innovations.

“We apply multi-omics machine learning models — including random forests, k-nearest neighbors and support vector machines –– trained on plastic-specific datasets that integrate gene sequences, protein structures, gene synteny and protein–protein interactions. We also incorporate advanced AI methods such as recurrent, deep and graph neural networks to analyze 3D protein structures. Alongside these plastic-specific datasets, we source additional protein data from the Protein Data Bank, UniProtKB and AlphaFold. These models help identify previously unrecognized genes with the potential to degrade plastics like polyethylene and bioplastics,” explains Kenneth DeMonn, a M.S. computer science alumnus, who is currently pursuing a graduate degree in biology.

“Essentially, this research bridges prediction and application. Since most plastics are synthetic, we aim to identify enzymes that can degrade them, test these enzymes in real-world applications, and eventually offer a bioremediation system design for tackling plastic pollution,” adds Emily Vue, an undergraduate student majoring in bioengineering.

|

|---|

| Dr. Battistuzzi's students, Muhammad Bilal, Kenneth DeMonn and Emily Vue, work on diverse projects that span topics from plastic degradation to pangenome analysis. |

Along with her CC Energy Consulting, OU and University of Cincinnati collaborators, Dr. Battistuzzi now set her eyes on the development of a novel computational model to identify candidate unknown genes in plastic degradation. A proposed project, “An Integrated Omics-based Machine Learning Approach to Identify Unknown Gene Functions for Plastics Degradation,” targets engineering microbes and enzymes able to tackle plastic pollution.

“By converting molecular data into insights Dr. Battistuzzi’s work creates the scaffolding for new therapeutics and biotechnologies as well as deeper understanding of evolutionary adaptation in a changing biosphere,” says Shailesh Lal, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Bioengineering and principal investigator of the project “The Characterization of RNA Binding Motif Protein 48 (RBM48) in U12 Intron Splicing, Cellular Differentiation, and Development." Gerard Madlambayan, Ph.D., professor of bioengineering and biological sciences, and Dr. Battistuzzi serve as co-principal investigators.

Dr. Lal’s previous study of the RBM48 gene, originally identified in corn, established a connection between maize genetics and the etiology of human cancer, revealing genetic pathways between plants and humans. The newly approved grant aims to understand how RBM48 helps control a key genetic process ¬– known as minor intron splicing –– essential for healthy cell development in both plants and humans. By leveraging advanced gene-editing and genomic analysis techniques. Dr. Battistuzzi will provide bioinformatics support to uncover the genetic mechanisms behind these discoveries.

“This introduces a paradigm shift in our understanding of human disease as knowledge can be gained by surpassing evolutionary boundaries. The project relies on large amounts of RNA sequencing data to measure gene expression and identify changes in splicing, which need to be organized and analyzed through computational pipelines,” she says.

As microorganisms drive key processes from nutrient cycling to biodegradation and bioremediation, it is essential to harness their capabilities in order to advance sustainable development and improve public health. Yet, Dr. Battistuzzi’s story reveals that computational bioengineering is much more than data and code –– it is about looking into the unknown and redefining possibility.

Dr. Battistuzzi can be reached at [email protected]

December 19, 2025

December 19, 2025

By Arina Bokas

By Arina Bokas