Where Have all the Chronic Illness Patients Gone

COVID-19 is squeezing out chronic illness patients

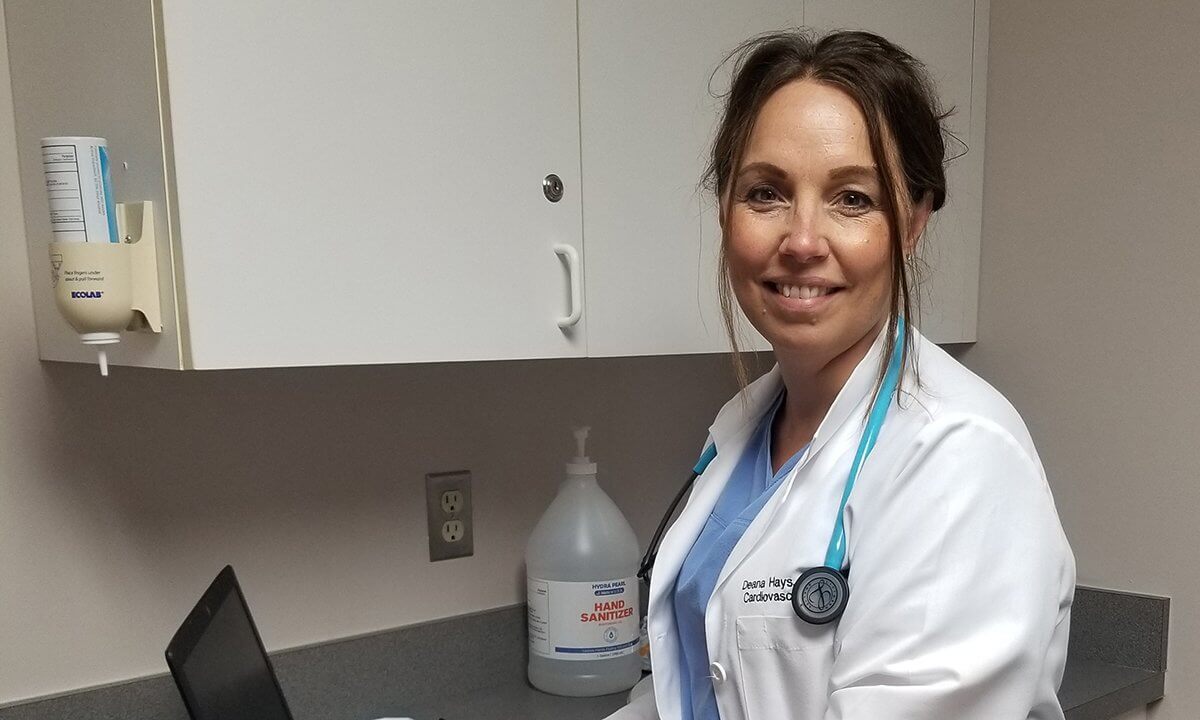

Deana Hays, DNP, RN, is an assistant professor in the School of Nursing. She has worked in the chronic care setting for more than a decade and experienced significant, and unsettling, changes to the population she treats and the healthcare delivery model amidst the COVID-19 pandemic and state’s shelter in place mandate.

The pandemic has altered the way healthcare has been practiced. The mitigation measures had not only altered personal lives, but also quickly changed the way that healthcare was delivered. Patients who presented with COVID-19 symptoms had replaced the acute conditions that once commonly presented to hospital Emergency Departments.

The introduction of this novel virus had also dramatically affected primary care and specialty clinics, which had closed or experienced decreased patient volumes. Once the stay-at-home order took effect, practitioners quickly experienced a rapid decline in patient volume despite aggressive mitigation measures. How would chronic diseases be managed in the future should we face another pandemic? Most of Hays’ patients had at least two chronic conditions that required regular monitoring with appointments every three to six months to properly manage their chronic disease and prevent disease exacerbations and hospitalizations.

Hays said, “We attempted telehealth visits, yet we continued to see a decline in patient volume. Patients were canceling appointments and did not participate in telehealth visits. I found many of my patients needed to understand what occurs during a telehealth visit before giving their consent to proceed. Telehealth is not a new way of delivering care, but it has not been widely used in primary care and specialty clinics, particularly in the suburbs and urban areas.”

This concerned Hays. She wondered what would happen to those with chronic disease if hospitals were seeing such high volumes of patients with COVID-19? For instance, a patient on a blood thinner required routine blood draws every two to four weeks. Those results would assist clinicians in proper dosing of the medication. Some patients were able to check their levels at home, however, there were others who needed to go into the office. If they were now avoiding labs for fear of COVID-19, what would patients do when they had levels that were too high (increasing chances for bleeding) or too low (meaning the medication is not as effective )?

With the added complexities, the pandemic caused her to question how professionals might change their approach in the future should another pandemic strike. Hays noted, “We must rethink how we manage chronic conditions and provide care for these patients.”

She went on to note several options. One option would be to expand telehealth services, which had been shown to be an effective approach in other chronic conditions such as mental health. In her own experience, the sudden rush to move patients to telehealth services left patients confused. Instead of seeing an increase in the number of patients using these services, she saw a rapid decline.

Hays added, “We need to educate the public on the value of telehealth services and embrace it as an option to manage patients with chronic conditions. We need to expand internet options for those who reside in underserved and rural areas to allow for better expansion of telehealth services. Clinicians need training on how to incorporate telehealth services into their clinic operations. And we need to publish evidence-based guidelines on how to utilize telehealth services in the management of chronic disease."

Hays called for clinicians to embrace technology that patients could use to help detect if they were headed for trouble. She asserted that there is a great opportunity for clinicians to collaborate with IT to develop easy-to-use apps for patients with common chronic conditions to help them manage or detect worsening of their disease.

“We cannot solely rely on in-person visits to help keep people healthy or keep them out of the hospital. We need to broaden our approach to care. And healthcare experts (nurses) should be on the frontlines of driving these decisions,” said Hays.

December 03, 2020

December 03, 2020

By Deana Hays

By Deana Hays