Center for Evolutionary Psychological Science

The mission of the Center for Evolutionary Psychological Science (CEPS) at Oakland University (OU) is to promote and support evolutionary psychological research and education at OU, to recruit and retain outstanding evolutionary psychological scientists, to facilitate collaborative evolutionary psychological research projects, and to develop gift, grant, and contract support for evolutionary psychological science research programs, graduate and undergraduate training, as well as core facilities and equipment. The CEPS will provide opportunities for community engagement, professional development, and mechanisms by which to enhance student success and the research portfolio of OU faculty, undergraduate, graduate, and post-doctoral students.

Broader societal impact: With a focus on identifying how our evolutionary past shaped our modern psychology and behavior, evolutionary psychological science provides a framework for understanding and addressing social problems including crime, violence, war, racism, and domestic abuse, while also providing a framework for increasing societal and individual health and well-being. The CEPS will provide a centerpiece for leveraging knowledge about our evolutionary past to improving lives in the present and future.

Todd K. Shackelford, Founding Director (Distinguished Professor and Chair, Psychology, OU), 2020-Present

The Director is appointed by the CAS Dean for a term of five years and is responsible for leading the Center in all matters, including research, instruction, service, and community engagement.

BIOSOCIAL CRIMINOLOGY Online Continuing Education Event - Friday, May 9, 2025 from 9-5 pm / Seattle University Crime and Justice Research Center

Transcript

>> Hi. Thank you for joining us today. I'm Viviana Weekes-Shackleford and I am here with the Wellness Warriors to talk with you about Evolutionary Psychology and its possible applications to mental health issues. I am an evolutionary psychologist, and I received my PhD in 2011 in Evolutionary Developmental Psychology. I am currently a faculty member in the Department of Psychology here at Oakland University. I also am the co-director of the evolutionary psychology lab. And in that lab, we, along with Dr. Todd Shackelford, we work with graduate students and advanced undergraduate students who are interested in learning about the research aspect of a psychology degree. I am also the Outreach Coordinator for the Center for Evolutionary Psychological Sciences. And I will tell you a little bit more about that center and just a few minutes. My research interests are quite vast. I enjoy research and I enjoy thinking a lot especially about evolutionary psychology and its applications. I'm Forrest bias, but I am just fascinated and intrigued and blown away by the complexity of our brains and how it affects, and how it's related to the behaviors that we engage in, behaviors that we see all around us. So with that, I am going to switch gears and share some slides and some information with you. So just bear with me for just a second, so that I can do that.

Now that ready.

So as I mentioned, I will be talking to you about evolutionary psychology today. I am, of course, a faculty member here at Oakland University and representing today the Center for Evolutionary Psychological Sciences. And of course, this is my pleasure to be here today with Wellness Warriors and engaging in this important project. And I must give a shout out to the Wellness lawyers. I'm sure they don't hear it enough, but I thank you for all of the things that you are seeking to do with this group. It's an act of care community. And I would argue consensus. Consensus in the sense that you guys are acknowledging that the more we know it's possible, that might be a little bit better in moving that progress line forward.

So before I go into the nuts and bolts of the presentation, I would like to just share with you a little bit about our center, Evolutionary Psychological Sciences. Is a relatively new development. It was approved in 2020. It's housed in the College of Arts and Sciences here at Oakland University. The founding director is Dr. Todd Shackelford, who is also a distinguished Professor and Chair here in psychology at Oakland University. Some of the goals and underlying mission of the Evolutionary Psychological Sciences in the center, more specifically, is to promote and support evolutionary psychological research, to also recruit evolutionary psychologists and scientists, and I would say good scientists, not just evolutionary, but also to facilitate collaborative research projects, to fund evolutionary focused research programs, whether it's by graduate students or undergraduate students. In one of the other areas that I'm most excited about, or the center is to provide opportunities for community engagement and to share and professional development and also to encourage students success. So part of our goal is to reach out, and of course, locally, nationally, and internationally, we have quite a list of external faculty members and academics and clinicians that are on the advisory board for the center. So we're pleased with that. We also intend to provide educational opportunities for the community and for whoever is interested, really like seminars, summer camps, and certificate programs. We also aim to fund innovative research projects and to organize and host different events by evolutionarily informed psychologists and including things like interdisciplinary conferences. So I'm going to start here by highlighting a quote from a book that I read this past summer. And it's called The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defensive Truth. The quote is, ''Acquiring knowledge as a conversation, not a destination.'' That quote, it's really resonated with me because and of course I didn't realize my take on this, which is obtaining knowledge and sharing knowledge at something that we do. The knowledge that we obtain and build, it becomes part of our knowledge base as a whole, as a society, as a group. And the other thing that I wanted to share with you is my philosophy. Because philosophy of teaching and sharing knowledge and having a discussion about sometimes difficult topics. And that is sharing what I know. Of course I don't have all the answers. I don't know everything. But sharing what I know using the tools that I have. Sharing that with you, learning what you know, where are you trying to meet you? Somewhere in-between or so that we can be on the same page so that we can have discussions and make progress in our understanding and our knowledge base. And also asking questions myself. I have tons of questions usually by the end of the day. Even though I spend most of the trying to find answers, I wind up with more questions if that's okay. And so that collectively we add to our knowledge base we have in society and our social roles are so many roles that we adhere to that really aware of just to keep things in place, cooperating and just keeping our being able to get through the day. You'll notice here at the bottom of this slide a few words like evidence, science, culture, that's experienced society reality. As always creating this slide, it just occurred to me. What are some words that might capture part of what I am including in this presentation and what are important words that capture some of the important things that I think are relevant to this discussion. So hopefully that makes sense to you. So I'm going to jump right into evolutionary psychology. So what do we do as evolutionary psychologists. You'll see over here on the left part of your screen the smartphone. Evolutionary psychologists see the mind being made up of psychological mechanisms. And we use a smartphone analogy. I didn't come up with it, but I do use it because, I think it does a wonderful job at describing the similarities in the way we describe psychological mechanisms. If we look at the calendar app, the calendar app was designed to deal with problems that are associated with organization, planning, keeping appointments in line and so forth. That calendar app is going to do best at calendar things compared to, let's just say the Target app. The Target app, is going to work better at solving problems that are associated with shopping at Target. And it's not going to do very well at solving problems associated with your calendar.

Similarly, the Costco app is not going to solve problems associated with the Target app. And we understand that these apps were designed specifically to deal with the specific problem that it's fixing, where that it's dealing with. And so evolutionary psychologists think about the mind in a very similar way, but we don't talk about apps. We talk about adaptations instead. So what the crux there is that these adaptations that we are talking about of the mind, are a result of the process of evolution by natural selection. We use an evolutionary psychological approach as a theoretical framework to understanding how the mind works. So if you take a look here, we've got these adaptations. You can think about them in terms of app. I think it's a really good analogy. But we have maybe perhaps a cheating app where we are very sensitive to cues around us, where individuals might be cheating, whether it's a loved one that is cheating or if someone is cheating. And again, for the most part, I think there's quite a bit of evidence and I think I don't have to show you the evidence, but most people don't like cheaters. And so we are very sensitive to any accused of cheating. And if you think about again, going back to the smartphone, if you think about cheating and perhaps the mechanism, the adaptation that deals with hunger and nutrients and so forth. This hunger app is not going to be as helpful in issues that come about from surrounding cheating. We don't expect that and there's no reason to expect that would be the case. So just like these smartphone apps are specifically designed to deal with problems that they were designed to deal with, so too are the psychological adaptations that we have in our brain that guide a lot of our behavior and thinking on a daily basis. So some other apps or adaptations that we can think about or cooperation. We are very social and socially complex species.

Part of our design of the mind is to strategize and maneuver through our social groups. Most of the time, of course, we want to cooperate. Same with disgust, there are mechanisms in place that can direct our behaviors to discuss as a cue that we might want to engage in a different route or do something different. Also, this little flashy mechanism I like to call mechanism of love, where it, again, deals with problems associated with distributing our love or care or investment and those around us, and same thing with morality. These are just a few of the mechanisms where there's quite a bit of research that supports this idea. But there are certainly quite a bit more. We have this picture of this lens here because I also think it's a wonderful way to think about evolutionary psychology that it's a lens that we use to investigate behavior. It is useful, another analogy to think about and include as you think about some of the things that we'll talk about throughout this presentation. This next slide here expands a little bit more about these psychological mechanisms with the mind, and this speaks to how they work. Evolutionary psychologists focus on typically the ultimate explanations for different types of behaviors. That is often compared to proximate level explanations, which are explanations that you probably think of and I think of when we're asked a question like, why do mothers care for their kids? Approximate explanation might be something like, well, we love them. But as an evolutionary psychologists, it's a wonderful response and it makes total sense. It doesn't really tell us much about the evolved psychology involved.

Another level of explanation that could be used is this developmental explanation where we've learned that it's important to care for our children. Of course, there are social consequences, there are many, quite a few that I can think of off the top of my head, consequences for not carrying rear children. One could argue that, well, we've learned that it's really important and it's an effective tool to help your kids along, to care for them. Another level of explanation is the following genetic explanation.

Caring for young is part of an evolutionary history. This is the kind of behaviors that mammals engage with.

It could be more complex than that, but that's just one phylogenetic explanation. We're evolutionary psychologists turned too often is dysfunctional or ultimate explanation that gets at the evolutionary history and the contexts that are involved. An ultimate explanation for why mothers care for their children is because they share genes with their children. I know it's not very pretty scenario, but it moves us back down the line for deeper and richer understanding of what is going on when we talk about care for kids and love for kids. Another example that is often used is the question like why do we grow calluses. Well, a proximate explanation is lifting weights. That's been lifting weights or doing gardening. The resulting consequence is an area of callus is growing there. A developmental explanation might be something like, well, thick skin grows in areas when you do a lot of work. Phylogenetic, it's a consequence of just being human, that any repeated friction causes a callus. But in evolutionary or ultimate explanation might be something along the lines of, well, there's an evolutionary history that those areas that experience repeated friction, one way to prevent infection or further damage to the area as to be able to counter this. That functional or ultimate explanation links nicely with survival and reproduction. That's where evolutionary psychologists principal interests lie. Of course, there are evolutionary psychologists that evolutionary developmental psychologists and evolutionary social psychologists. But even with those areas, there is this underlying understanding or the framework is still there, or their focus of their research might be in a more proximate level, but it doesn't mean that they're not interested or that it's not important to understand the ultimate explanation for different things. Another example of a question might be, why do we feel romantic jealousy? Well, approximate explanation might be something like, well, my partner is spending more time or it appears that my partner was cheating on me. A developmental explanation might be something like, well, when I feel jealousy, it might be a learned thing that if I express some level of jealousy, that means that I care, showing my partner that I care. A phylogenetic explanation could be something like, well, this is part of our human evolutionary history that we engage in upset or it guides our behavior. That it's important to express these things if we want to maintain mate. More of an ultimate explanation for why this is that is, how can we bring that link, how can we link it with problems that directly, or an explanation that fits more in line with a direct line to problems associated with survival and reproduction? In this case, why do we feel romantic jealousy, what might be an ultimate explanation? Well, the ultimate explanation is, well, the goal is to deter or stop any cheating because if our partner is cheating, that is whether it's investing time, money, in another individual, those are benefits or investment that you could be receiving which in turn affects your survival and reproduction. Again, just keep in mind that I'm using these as examples and these are simplified as ways of thinking about it. But my goal here is just communicate some of the details and just an overarching idea of how evolutionary psychologists approach different areas. Hopefully, as we go on in the presentation, some of this will become a little more clear. Another useful way of thinking about how the mechanisms of the mind to work is this setup. This is something that I've used for decades myself. But I also think that when I use this, I do get positive feedback. It does make things a little bit easier to understand. Again, with that same example, why do we grow calluses? If we use this paradigm here to understand it, I think it's helpful. We have that repeated friction, which we would call our input, and then this box here represents a decision rules and that is where a good chunk of the processing occurs. It's doing all the proper calculations. If this, then that. If A, then B. I'm sure it's not that simple, but the point is, is where these calculations occur. Then what is the output? The output might be like one output of repeated friction to an area could be a catalyst. Then from that output, we know that different behaviors can be approached. Same thing with why do we get jealous and more of a psychological example here, we might have queues of cheating, that is the input. We have these evolved psychological mechanisms in our minds. We get a cue that perhaps our partner is cheating, it might be a subtle cue, it might be an in-your-face type of cue. But let's just call them cues of cheating. We have our decision rules right here. These decision rules are going to take things into consideration. Was it is it just a soul cue? Is this direct evidence? It's taking those things into consideration, and again, making those, if this, then that type of calculations throughout an a much more complicated fashion, I imagine. The goal is to stop cheating and to prevent it to stop it. What that behavior looks like in the end is going to depend on many things. Sorry, I jumped ahead. It's going to depend on what those cues were, the contexts in which it happened.

Then the output is going to vary as well. One output or one response to this might be something just a simple phone call, I love you, or it could be a break- up. It could be talking with others about your situation. The point is that it's really not simple, but this is a simple framework to think about how these mechanisms operate. Let's switch gears a little bit and take you back to just a quick snapshot of historical sense of where did we get these ideas from? Well, I think most people, when we say evolutionary or evolution and we think Charles Darwin, and that's correct. Charles Darwin is credited with bringing together this idea of evolution by natural selection. We know that evolution just means change over time. This is something that's been thought of for hundreds of years before Darwin. You know how to species come to be, how are we different from other animals and so forth. But Charles Darwin is recognized for his, The Origin of Species and which he organized and put together his ideas to describe the process, to describe how evolution happens. I do have Alfred Russel Wallace up here because he is not often thought of or recognized as a contributing individual to our understanding of evolution by natural selection. But he also, around the same time, came up with independently the same ideas that Charles Darwin did. But Charles Darwin made it to publication a little bit quicker. But I like to include it here. As I mentioned, there were discussions of evolution for at least 2,500 years prior to Darwin's publication and with this organization of his thoughts and explanation for how evolution occurs, it really is the foundation for modern-day biology and it is recognized and used.

It is pretty much a fact in biology. It's recently, meaning last few decades, where the application of evolution by natural selection was applied to humans. There are three components that are necessary for natural selection to operate. The three components are variation, inheritance, and differential reproduction. When we talk about these three components, I've got this figure here that captures these ideas in a colorful way. We've got our green beetles and our orange beetles. What you see here are these crows that are just arbitrarily picking these green. It looks like it's arbitrary and maybe they reduce your media or I don't know. But they are choosing these green beetles over the orange beetles. Over generations what happens is these orange ones, it appears that they are surviving while the green ones are being eaten a lot more. With this continuation of the orange beetles being more successful and surviving and reproducing, if it's a heritable component that is color, if it's something that's heritable, then it will be passed on to later generations. What you see here in the spinal area is more orange beetles. The crows will either, move on to an area that has other green beetles or they might start eating the orange ones, who knows. The point is that, this an arbitrary thing, in terms of color. But what we have are exactly what natural selection needs in order to operate. Variation, we have variation in the colors of the beetles. We have inheritance, it's something that is passed on from one generation to the next. Then there's differential reproduction. That is that the color of these beetles, it matters the orange ones tend to survive and also reproduce. Perfect scenario for natural selection to operate.

We'll move on to sexual selection, which is another aspect of evolution by natural selection. Charles Darwin was perplexed about why the peacock has this wonderful tail, now elaborate colorful tail and we don't see something like that in the pea hen, this is quite an extreme display. In the end, what Darwin realized was that, this is something that is an indicator to females of the males health and immune system. In essence, his genetic quality and again, I'm loosely using these words. The presence of something so extravagant, according to Charles Darwin or to the principles of sexual selection is that one powerful drive for this to happen is female preference. It's an indicator to females about these males and his ability. There is evidence research showing that these peacocks, peacocks with the most colorful transia and colorful plumage and so forth, actually have more mating opportunities than those peacocks who have less extravagant and less colorful tail. It's a really interesting thing to think about. I do have some other examples of other birds that you might see. Mallard ducks we see all over. We can most of the time tell with a lot of bird species which individual is the male and which one is a female. Here we've got these mallard ducks that the males are a lot more colorful than the females. Bluebird, same thing. There is some blue on this female bluebird, but the male bird is a lot more brighter. It looks a little bit bigger. I can't recall which duck this is deck species, but again, same thing that it's extravagant display of colors and features that are just information for females to take into consideration as they explore meeting opportunities. Also, we've got the male cardinal with a lot brighter red and the female cardinal has a lot less red. But my point here is to highlight the importance of sexual selection as explored by Charles Darwin and his contribution to understanding natural selection and evolution generally. Here we've got the modern synthesis and Gregor Mendel is recognized for his contributions to what we call modern-day genetics. He was around and alive during the time of Charles Darwin. But he was off his camp doing his exploration and Charles Darwin was off doing his exploration and it wasn't until about the mid 20th century that the two fields were put together and it was called the modern synthesis. There were also other researchers involved in this as well. But again, the foundation for a lot of the biological sciences and our understanding of genetics and the progress that we've made. It's been made because of these contributions by these wonderful researchers and scientists. What are some misconceptions? It's not uncommon that when the terms evolution and evolution by natural selection are used, there are some misconceptions that come to mind and I've included two of them that I think are quite often heard. The first one is behavior is genetically determined. If evolutionary is true, if we say that our behavior, and therefore our psychology is a result of evolution by natural selection, then that means the things that we do and the things that we think are it's genetically determined. It is a misconception about evolutionary thinking and I will use the same examples that I've been using on a little bit earlier, so repeated friction and or callous example. We, in order for a callous to appear, we need to have that repeated friction. While there may be a genetic inherent genetic predisposition or some wiring that is available, once it's part of our genetic makeup. Calluses don't just appear. We have to have some input or repeated friction in order for the callous to appear. The idea that any behavior or mechanism of the mind or behaviors that are a result of things in our mind, it just doesn't hold much water. This is a physiological example. But let's move on to a psychological example with jealousy. If it's evolutionary, that means that the behavior can't change and that means that any resulting behavior that is derived from this evolved psychology that we have, it means that it's okay and that it's a status quo. It can't be changed. But let's go on with this example of cheating or jealousy. In order to stop a behavior or stop your partner from cheating or intervene or learn more about what you think might be happening with your partner, we need to have queues that are put into this process. So we don't go with that example, we don't just turn to a partner and say, you're cheating without having some cues to trigger that thinking.

Here, the point is, I understand that with this example on this misconception, I'll jump right to it so it, so behavior can change. Let's just say we're talking about male violence towards women in relationships. If a male thinks that his partner's cheating, and he not consciously, or we'll leave that part out, but let's say that he engages in violent or abusive behavior, if it's evolutionary and we say that it is, and there's evidence to show this, that means that he can't change his behavior if he thinks she's cheating, then it's okay for him to engage in that violence and abuse. Absolutely 100%, no, that is not the case. In order for that behavior to occur, there has to be some input. We have cues of cheating, we have our decision rules, and we take things into consideration, not irrelevant. There are social consequences to engaging in abusive behavior, or it can actually hurt the relationship if you accuse your partner is cheating and they are not cheating. My point here is that it just can't be the case that it doesn't change. That I cannot change because we've got these big brains for a reason. We don't just haphazardly lash out if we have any just a subtle cue built into these mechanisms of the mind, or other mechanisms of the line that takes into consideration the level of the cue. What are the considerations? What exactly is the contexts in which this is happening? It's much more complex than A happens, then B happens, and then C happens. Unfortunately, I think actually if that happened, we might have a better way of fixing a lot of the problems that we have as a society. But it doesn't happen that way. Not even from an evolutionary perspective.

What are some products of evolution? There are three primary products of evolution and they are adaptations, byproducts and noise. Adaptations, you've already heard me talk about this with the mechanisms of the mind, we think of adaptations as the analogy those or those apps. What are adaptations? What are they for? They are for solving problems or any challenge during our evolutionary history that affected our survival or reproduction. You can think of the heart as an anatomical or physiological and has an anatomical adaptation that circulates blood. The primary function, at least as we know it today, for the heart, is to circulate blood throughout our body. That's what it was designed for and that's why it works better than your liver for such a purpose. Sweat is a physiological adaptation that regulates your body temperature. Sexual arousal is a psychological adaptation that motivates sexual behavior. I'm using these words like anatomical, physiological, psychological as the primary contexts in which these different examples are used, but certainly sweat. There's also other issues involved with sweat and sexual arousal as well. But it's just a highlight that you can have adaptations that physiological level, neurological level, anatomical level, psychological level, etc. One thing to note is that not all products of natural selection or adaptations, so we go on to the byproducts, which byproducts are traits that are associated with adaptations. You can't have a byproduct if we don't have an adaptation and their incidentally linked to these adaptations. One thing to note is that identifying a byproduct is just as important and just as rigorous as identifying adaptations because it also requires you to identify an adaptation first, for which that byproduct might be identified. The human navel is a wonderful way to talk about this in the whiteness of bones. The human navel, we know the human navel itself is a byproduct of the adaptation of the umbilical cord or which mothers and their fetuses enjoy the interaction of blood and nutrients through the umbilical cord. The navel is a byproduct of that, that's evidence of that relationship that you had with your mother. The by-product of the navel being byproduct is it's an incidental aspect of the adaptation of the umbilical cord. The human navel does not contribute to survival or reproduction, does nothing for it. Same with the whiteness of bones. The color of your bones as far as we know, are a result of the stuff that makes up the bone. It's incidental and it does not have any independent effects, there are direct effects to survival and reproduction. Noise, which is the third product that we'll be talking about today, or random effects. These are just even a step further. They cannot solve any adaptive problems and are typically produced by mutations. Noise, unlike a byproduct, is not linked to an adaptive aspect of a trait. We can think back to that human navel example. The random shape of an individual's navel is, would be noise. We have the umbilical cord as the adaptation. The byproduct would be the navel itself, the scarring. Then the noise would be something like the shape of the table right here in the US, we talk about inies and outies. At least that's what I'm aware of. But there may be other ways of describing the shape, but it really has nothing to do with the adaptive nature of the umbilical cord. Let's talk about these evolutionary time lags and environment of evolutionary adaptiveness and certainly, come up a little bit later so pay attention to these wonderful fries, cheeseburgers and pizzas. [LAUGHTER] When we talk about evolutionary psychology, we have to think of our minds today as a product of our ancestral history. It took millions of years for our brains to evolve and the stuff that makes up our mind to evolve.

What that means is that our brains evolve at a different time and because it's taken such a very slow and gradual process although his argument about different aspects of that, the modern day environment is quite different than the ancestral environment in which our brains and our psychology evolved.

There is historical, anthropological, paleontological evidence that our ancestral past was one in which we operated in small bands of very closely related individuals. There were times where we did not have access to consistent food or nutrients and one way to deal with that inconsistency of our availability of foods and nutrients is to eat whenever you can and the fattier or better. While that may have worked clearly it did because we're here today, it worked during our ancestral environments. Today, these types of foods are at every corner of every [LAUGHTER] intersection making it very difficult to say no to these types of foods.

The way we think about this is that there's this evolutionary mismatch so we've got these ancestral brains, but we are living in a modern environment where now there's really no concern. For the most part I understand that there are nutritional instances where people do not have access or don't have the means to have regular nutrition but we're talking just on average and the ability to say no to these things is very difficult and hence we have quite high numbers of obesity and diabetes and clogged arteries and things associated with this mismatch of our ancestral brains in a current modern environment. What are some domains or areas that evolutionary psychology has played a role in and has informed. This is not an exhaustive list but these are the most common or anything. There's a lot of research across the board but here are some common areas that are informed by evolutionary thinking. Sex differences, why we might expect sex differences in particular areas between men and women, aggression, meeting and romantic relationships, family relationships, cooperation, social conflict status, hierarchies and morality? In thinking about these different domains here, these are kind of, you can easily relate them to the social sciences and so forth. But other areas have also been informed and it's growing in other areas that may not be clearly linked to the social science but, I mean, we could make an argument for drawing these in. But public policy is now being informed by evolutionary thinking. Law is also being informed and a lot more interests in framework application to thinking about the way the laws are created, also, thinking about the sentencing and types of criminal treatment, differences in the way that women and men are treated and the way that they are incarcerated and so forth. Certainly, economics and consumerism, those are areas also that have recently just skyrocketed in the application of evolutionary thinking to these areas. I have mental health here in green because this's what the focus is today but I do want to point out that the application or just thinking about applying evolutionary thinking to the mental health framework or mental health areas are issues is nothing new, it's been going on for decades. It's just recently I myself have been thinking and it's grown very interested in understanding where evolutionary psychology is in its application to mental health issues and can we benefit from it? I'm going to take you on this little ride with me. The call for applying an evolutionary framework to mental health issues, like I said, is nothing new. I do have this paper posted here just as an example of, I'm not just making this up. This is something that is actually out there [LAUGHTER] in research and people are. Researchers in the mental health are also quite interested and, I think, pushing the pedal on the need for a different way of thinking about mental health issues. I'm going to just pull out a sentence or two here that highlights this. We'll use several previous applications of evolutionary theory that highlight the ways in which psychiatric conditions may persist despite and because of natural selection. Again, highlighting this idea and this is just my point here that, again, this is nothing new that I'm saying. I'm just bringing my thoughts together and sharing this with you. One lesson from the evolutionary approach is that some conditions currently classified as disorders because they cause distress and impairment may actually be caused by functioning adaptations operating normally as designed by natural selection. When we think about disorders of the mind, like what we call disorders and I'm using air quotes here, disorders of the mind like depression or schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, the proposal that has been consistent from an evolutionary perspective is that these expressions or these constructs that we have defined. We define what depression is.

Perhaps they are the output of, or they themselves might be the result of a normal brain functioning. Let's see. Thus, the evolutionary approach suggests that psychiatry should sometimes think differently about distress and impairment. The complexity of the human brain, including normal functioning and potential for dysfunctions, has developed [NOISE] evolutionary time and has been shaped by natural selection. Understanding the evolutionary origins of psychiatric conditions is therefore a crucial component to a complete understanding of its etiology. Again, just highlighting the point here that, look, I'm not saying anything new. The application and thinking of evolutionary psychology, or evolutionary thinking to the framework, and applying the framework to psychiatry, mental health conditions, psychopathology generally, has been ongoing, and there have been a number of theories that have been put forward that have this same approach that what we describe, we meaning what we hear typically, whether it's social media or just in discussions. We might actually read these kinds of things in academics as well, that disorders such as depression. We see them as dysfunctions, or there's something wrong. But my understanding at this point of literature and evolutionary thinkers is that, it might be time to rethink how we as a society think about these, again, loosely saying here, disorders. David Buss, in his textbook that uses for introductory evolutionary thinking, helped me with this. It organized my thoughts in putting this together. The question that I have here is, can evolutionary psychology inform our understanding of mental health? I say, yes, I am biased. I understand that. But bear with me here as we work through this and I'd be curious after the talk for any feedback and to continue a conversation about this. I don't have the answers, but maybe you do, so I'd love to be enlightened. The DSM, or the DSM-4, or five, I forget where they're at at this point. When we think about disorders or depression, anxiety, and so forth, we think disorder, dysfunction, abnormal, maladaptive. There's something wrong is the bottom line. But when we apply this evolutionary thinking to this issue, a few questions can be raised. Could it be that mental health disorders, and I'm doing air quotes, you see quotes there. Could it be the case that mental health disorders, what we call them, are functioning just as they're supposed to, and that the possible explanation for why it appears as a mental health disorder is that there's a discrepancy between ancestral and modern environments? One example that, I think, David Buss uses in talking about this topic is, which is a wonderful one, postpartum depression, with women that in our ancestral environments, we operated and moved around in bands of close relatives and extended relatives. Essentially, we had a tight-knit support group and so forth. One of the hallmarks of identifying postpartum depression is not having a support system in our modern environment. That's one of the key features or key predictors of postpartum depression. This highlights, or at least I think is a good example, or a good way of thinking about how something like postpartum depression, we call a dysfunction or abnormal psychological functioning. In our modern environment, it's actually working as it's supposed to, that women who have more of a support system wind up not having just a lower incidents of postpartum depression. Whereas women that have more of a social support system report less incidents of postpartum depression. For Number 2, could it be that mental health disorders are subject to normal errors? When we think about these adaptations of our mind, if we think about the heart, for example, which is a good physiological or anatomical example, the heart works most of the time as it should. If there are little errors that do occur, we aren't aware of those errors because they're probably just they don't affect anything else that we're aware of. We're not aware of what's happening. We understand that these patients have to work most of the time. It's never going to be perfect. Even the heart is not perfect. Sometimes there's electrical malfunction.

It's a natural on average level of operation. Errors will happen. Same could be true for these mental health disorders. It could be just these are normal functioning adaptations, and sometimes it's off-kilter, and it's just an error, but it doesn't mean from there, you're headed down this dark tunnel forever. Three, could it be the case that these mental health disorders or what we call mental health disorders are result of individual differences and subjective interpretation? The example that I like to use is if we have three individuals that have exactly the same car accident and they totaled her car, injuries, thank goodness. But the car is totaled. You can have one individual that goes into a depression. What am I going to do? This changes everything, and it's global sort of, oh, my. Then you can have another person who says that, well, that's okay, I'll ride my bike. I got a bike. It doesn't matter. Then you might also have someone that does also get upset. There's a response like, well, there's no car. Thank goodness, no one was hurt. I'm going to contact my insurance company, and we'll go from here, we'll get it all fixed. All three of these individuals are experiencing exactly the same situation, the upset or a life incident.

The description of depression is a result of that individual's subjective interpretation of what has happened. It doesn't mean that, given a car accident, someone will be depressed. There's a level of subjectivity to things that happen, is the point here. The fourth question that could be asked is, could it be the case that these mental health disorders are called as such because they lead to social harm? There are example that David Buss uses in his book is one of psychopathic behavior. Typically, we don't like that. We call that a bad thing. Psychopathic behavior, because we understand that that can harm us. Generally speaking, on average, psychopathic individuals cause harm. But we are defining what that means. It's not really getting at understanding the mechanisms of that, what we're calling a disorder. There are instances in which psychopathic behavior might be, and I'm not condoning any sort of violent behavior whatsoever, or psychopathic behavior generally, but we're just sticking to explanations and the exploration of these mechanisms have to go a little bit deeper. Sometimes you might have to ask difficult questions like, are there some times where psychopathic behavior might be relevant or useful? In what contexts might we expect that to occur? My point here without fourth one is that, we as a society are defining and calling different types of disorders bad or harmful, or maladaptive, or disordered, or dysfunction.

The argument is that we are not really getting at the root of the mechanisms that are involved here.

I'm going to switch gears again to build an argument for why it is time, I think, for a new look at thinking about mental health issues. This represents what you're seeing here, represents a pattern of symptom overlap in the DSM-IV. Here we've got these various dots that represent each of the symptoms that are listed here, mood disorders, anxiety disorders. I'm not going to read through every single one of them, but sleep disorders, personality disorders, disorders first diagnosed in infancy, childhood, and adolescence. Let me do how about another one? Substance related disorders, schizophrenia and so forth. There's quite a bit of disorders that are listed here. But what I'd like to bring your attention to is the pink dots, orange dots, and the green dots, which represent mood disorders, anxiety and substance abuse. The message here that I'm trying to convey is that we see these dots, and they represent where they fall within the DSM-IV in which chapters. What I want to bring your attention to is this mood disorders, anxiety, that we see around here, and then these green substance abuse disorders. These are all diagnosis and the DSM- IV.

What we see here is how they are clustered together and are also connected to each other. The point here is that when we talk about depression or anxiety or mood disorders, it's very rare that these symptoms or symptoms of these disorders, or we call disorders, are operating alone. We often hear that a lot of these disorders are co-morbid with a long list of, not necessarily a long list, but are often accompanied by other diagnoses or other symptoms that would lead to other diagnoses. The point is that this is a much more complex than labeling an individual with depression because depression, at least based on the symptoms that are associated with depression, could also be linked with anxiety or substance abuse disorders as well. This captures the complex nature of symptomology in the DSM. In this slide here, what I'm showing you is the percentage of people in the US who suffered from depression from 1990-2019. This is taken from Statista who they create statistics using data from a wide variety of national level survey collections like CDC, NIH, and so forth. This is a figure that I pulled and it's publicly accessible, so you can take a look at it yourself and read more about it if you would like. But my goal with this slide is to show how common it is and how common it has been since 1990s. This goes 1990, you'll see that right here through 2019, and my take on this is that while there may be differences, we can look from year-to-year, maybe some subtle differences as a whole, and it's a relatively stable label of depression, a stable phenomena that we see here. It ranges from, I think the lowest is 4.7 to, actually the highest is 4.93% of people reported being suffered from depression from 1990-2019. It's a relatively stable feature and it's not unique to the US. This is something that has been documented across the world. The World Health Organization also has quite a bit of data that is also publicly available that you can make that comparison and see for yourself. This is, I don't have it included here, not because it's not available or those as something different. It's just like you don't have it here, but you're welcome to explore that. Again, this is my take that we saw on the previous slide that it's complex and we also see that it's a common, at least this is my take that it is common and that we can also see this across cultures. Here is changes in mental stress among adults in the US from April 2022 to January 2021 by month, and so these individuals were asked about how stress has changed over the last month and what we see from April 20th to January 2021 is very similar pattern of findings. This is also from Statista. Same spiel there that it's their statistics using publicly available data, and what we see here, April 2020, we all know that COVID was a big part of our lives at that point, and so asking about the previous month, these participants reported 49% changes in mental stress, 35 present here and then we see a tapering off or a leveling out of stress levels, and so the idea here is speaking to stress. Higher stress means higher rates of depression.

We see this leveling out with more mental stress remaining stable. This next slide, we have percentages of respondents in the US who reported symptoms of depressive disorder in the last seven days or two weeks, and again we see the same pattern that we saw in that first from 1990-2019 and participants reporting being depressed. The same pattern where in 2020 we have this higher rates of depression in the last seven days to two weeks, and then as COVID became a little more normal part of our lives, we see a little bit of a tapering off. We do see a little peak here, and one could take a look and see what was going on during this time that might explain this peak, but if we envision a figure like this, you don't taking a step back and spreading it out a little bit further over the years, we might see that same pattern where yes, there are blips increases and decreases. But probably if we look a little bit deeper into those peaks and valleys, that there may be something going on socially that could explain why that's happening. But then we still come back to this tapering or a tamping down or a settling of this depressive symptoms. I'm going to switch gears a little bit to talk about suicide because often the top goes from about mental health disorders, we talk about what we have to prevent depression because depression leads to suicidal ideations. Suicidal ideation results in suicide. I will, I think in the next few slides I'll tell you why that might not be the case, but what I'd like to show here is one thing that's been consistent across studies and just a general trend since suicide has been documented is this relative difference between males, and females that males on average deliberately kill themselves at a much higher rate, or maybe not much higher, but a consistently higher rate than females, and this is just speaking to that. That's something that's relatively stable across time and across cultures. There are, again, when we do see deviations, there is probably something that is happening during that time around that population that could explain why there's the deviation, but this is what we typically find. We've got males here and I do have to point out that they look similar, but if you look here on this y-axis, these suicides per 100,000 individuals in a population, these numbers are quite a bit higher compared to the numbers on the female y-axis. We see 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, whereas with the highest rates being somewhere around maybe 42 or 43 suicides per 100,000 in the population. But for females, the highest rate is somewhere around 10 individuals per 100,000 in the population. Of course, for any instance of where individual deliberately kills themselves, it's an awful thing.

Anyone is devastating. But we do have to speak about differences. We do have to be about differences and talk about what is different in their psychologies that might help us with understanding why it happens, how it happens and so forth. We see here that there are the blue lines for both these figures are those that are 10-14. The black lines for both of these are 15-24, 25-54, or the gray lines. The red line is those individuals, 45-64, green 65-74, and yellow 75 and over. We see there are some differences, so if we take our yellow line, which are the 75-year-old individuals and older, we see that they are actually have the highest rates of suicide compared to the other age groups with males. For females, the highest rates are the individuals deliberately taking their lives. Are those individuals that are 45-64 years old. There are some differences.

Sometimes, I think when we hear about suicide in the social media and we don't often hear the nuances. These are important nuances, especially if we want to understand why this happens, how it happens, and so forth. We have to understand these nuances. It cannot be dismissed or ignored.

I thought this was a really interesting slide to include, because it speaks to our moral interpretation of suicide. If you look here, these are individuals reporting or answering the question, do you consider suicide morally acceptable or morally wrong? Morally acceptable is represented here in our blue section of these bars. The dark blue represent those who answered that, it's morally wrong. Then the gray at the top here of these bars are those who said that it's not a moral issue. What I think is really interesting here, and telling is that there's clearly a larger percentage of individuals report that suicide is morally wrong. Again, without being an expert on this question and morality specifically, if it's something that's morally wrong or morally not acceptable then it's probably something that we don't want to talk about. We often talk about the negative stigma surrounding suicide. One reason for why it might, that we have this continued negative stigma is, I would argue that it's related to our moral assessment of suicide.

For those who are interested in reducing that stigma, and would like to address it and try to change that, I think continuing to do what you're doing and talking about these things might be useful. But this might also explain why there's this negative stigma and it's really difficult to break. This might be standing in our way.

Evolutionary psychology, what does this mean? Where is the future of evolutionary psychology as it relates to mental health issues? The impact of evolutionary psychology on just general psychology has been just huge for decades now. The field has been just growing exponentially. Not just evolutionary psychology, but it's the framework that it uses to understanding human behavior as it's being applied in many disciplines or sub-disciplines, including medicine and law. Now, Cas Soper is someone who I've recently began exploring his writing and his thinking, he is a evolutionary psychologists and also a clinician. Cas Soper, he's put out a different way of thinking about using an evolutionary framework to understand psychopathology and suicide specifically. As I mentioned earlier, there are many theories or hypotheses that have been put forward that are informed by an evolutionary perspective to explain why there are mental health issues and things like depression and anxiety in bipolar disorder and so forth. What Cas Soper does is he proposes that psychopathology is an effort to thwart self induce lethal outcomes. So what? He uses his pain brain idea, which he says that it's unique to humans. The idea that at least there's no evidence over good evidence so far that other species, non-humans experience and are able to think about ending that pain forever. This is something that humans uniquely have. When we think about pain, if you bump your knee or you're having abdominal pain. What is pain for? Pain is used to motivate some behavior to minimize or address that pain where is it coming from, what it exactly does it hurt, what caused it? We want it to stop, to stop that pain. In Cas Soper's model of thinking is pain brain model. The brain, if you're having what he refers to as psychache. This is a term that's been used in psychology, and understanding mental health issues for some time. But he he describes as pain is, also is a psychache. We having psychological pain and oftentimes it's linked to social issues as a result of social consequences or things that are happening in an individual's life. The psychache or pain of your psychological pain, it's subject and triggers those same things that are triggered when you bump your knee or you have abdominal pain. You want it to stop. We want it to stop, we need to fix this. What silver proposes is that we have our brains that are, they must be developmentally ready, or there must be this cognitive threshold that has to be reached in order for the brain to affect responses. We don't see children's typically suffering from psychological pain or psychaches in the way that adolescents or young adults or even older adults experience. His argument is that they do not have the cognitive capacity to understand that one response is to deliberately in one's life. Of course, we understand that there are instances in which this happens where that happens. But it's very far and few between where it happens in each one of course is obviously devastating. Things like depression, anxiety, mood disorders are manifestations of what Cas Soper's zero anti-suicide defenses. If you think about depression, depression it tampes down your ability to coordinate, to think about exacting any permanent damage to oneself.

Anxiety is often invokes confusion and also panic and lack of clarity. Again, the attempt is to slow down this process. Same with mood disorders, that they are all manifestations of anti suicide defenses. One thing that you have to let go of is this idea that depression causes suicidal ideation, suicidal ideation causes suicide. According to Cas Soper and my understanding of literature at this point as well is that that yes, those things are related, there is a correlation between depression and suicidal ideation and depression and suicide risk. But what Cas Soper saying is that arrow is not a causal. We don't know the direction, we can't say for certain that it's depression that's causing suicidal ideation or suicide. There's no evidence to suggest that. One of the things that he indicates is that the majority of individuals with serious mental health disorders, and I'm doing air quotes as well, do not take their own lives. Most people who suffer traumatic life events as devastating as they could be for one individual or another, it's atypical for someone to deliberately end one's life, even in the face of horrible life trauma. Consistent with this idea, it's not something that is promoted or talked about in social media or in everyday conversations, is that there's an acknowledgment of this. Even at a clinician's level that there's an early increase in suicide risk as a depressive symptoms begin to leave. This is an awareness and an alert that practitioners and clinicians are aware of once this depression leaves. If you go with me here, that depression leaves and you have sudden energy. I got this. That's when clinicians are particularly attuned and understand that there is elevated risk for suicide risk at that point, when the depression is lifted, not during depression.

In a nutshell, what Cas Soper is suggesting here is that we have these evolve protective interventions. Like depression, like anxiety that are normal protective manifestations of our evolved psychology. They are interventions, and what they appear as is psychiatric disorders. We are calling them psychiatric disorders. I know it's a lot, they're packed in one slide, but just to take it away from evolutionary thinking for just a second.

Again, this is my thinking about this, that there is this implicit acknowledgment of problems that the area of mental health has in understanding mental health issues that we were stuck in labeling. Again, this is something that's really important and that I understand, especially as a researcher and scientists, that we do the best we can given the evidence that we have. But one of the things is a good feature and we know is a good feature of a theoretical approaches is it generates new ways of thinking and new questions that can be asked about the same old things.

I really think that this is an extension, a great example of a good theoretical framework because it is generating new ways of thinking and new questions about this topic. The National Institute of Health, they have this new initiative called the research domain criteria. I would go as far as to argue that in this framework, this initiative, they're admitting that we might have to go beyond the label of depression or anxiety or bipolar disorder as describing the state of individual's psyche. The RDoC framework provides an organizational structure for research that considers mental health and psychopathology in the context of major domains of basic human neural behavioral functioning rather than within established diagnostic categories. The framework currently includes six major functional domains. My point with this slide here in this figure from the National Institute of Health Care is that there is an acknowledgment here, this is my read that it's probably time to move on beyond the label. If we expect to reduce these symptoms and to address them in a better way than we might have to rethink the way we are approaching these symptoms or these labels that we're using. In this framework suggesting to take into consideration lifespan development, units of analysis. Are we looking at genes? There's these depressive disorders and anxiety. These are very heritable traits. Again, suggesting that it's part of our human nature. It doesn't mean that we have just let it go and accept it as it is. We can want to make people feel better. But in order to make people feel better, one approach maybe we should understand it a little bit better.

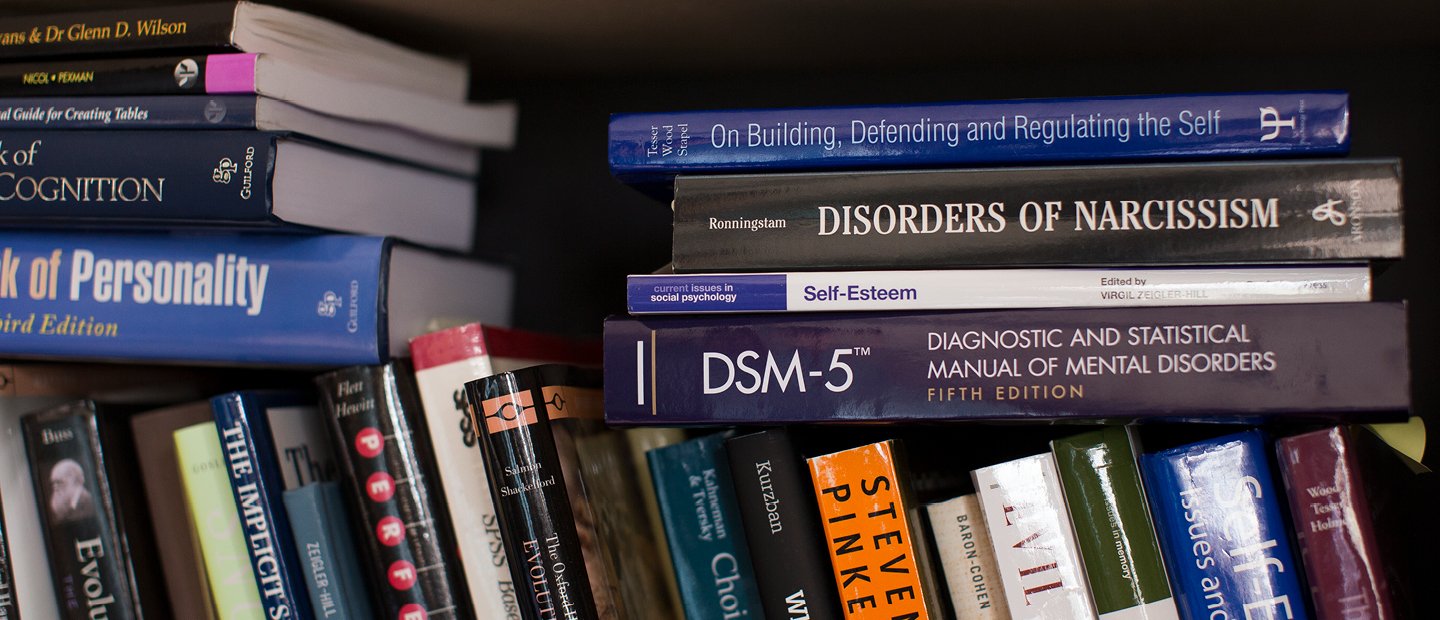

These are just to lighten the mood a little bit. These are some books that just to highlight in book format, the importance of including evolutionary thinking and some examples of evolutionary thinking as it applies to medicine and psychiatry. Randolph Nesse is often referred to as one of the major contributors to this area. Good Reasons for Feeling Bad is his most recent book, Insights from the Frontier of Evolutionary Psychiatry. Defining Mental Disorder by Jerome Wakefield and his critics. This is just a collection of a framework that Jerome Wakefield has put forward and then responses from philosophers, clinicians and so forth that they put together in a book which is really fascinating. Then also The Evolution of a Life Worth Living. This is a book written by Cas Soper, who I mentioned a little bit early, which is a phenomenal book. Then these are just some examples of other evolutionary informed books on psychiatry, Religious Beliefs in Medicine, so you can take a look at those. These are books that are must reads. If I had to pick a few, here are just a handful of them. If you're interested in learning more about evolutionary psychology these are wonderful starting places. David Buss, who is one of the founders of the field of evolutionary psychology. He's got a wonderful textbook that is often used. We use it here, Oakland University at an introductory level to share with students the field and where it is. One of his books, The Evolution of Desire or Richard Dawkins' The Selfish Gene is a great way to think about and learn about evolution by natural selection. Debra Lieberman and Carlton Patrick are also included in this book because it speaks to the evolutionary application of law as our history. [LAUGHTER] The Evolutionary Obligation to Law and then The Adapted Mind, again, the authors here are Jerome Barkow, Leda Cosmides and the late John Tooby, who the two of these individuals are also part of the group that we credit for founding the field of evolutionary psychology. Then Adaptation by Natural Selection also a wonderful book with a lot of insights in details about natural selection and how to identify adaptations and so forth. I mentioned a minute ago some of these authors or the founders of modern day evolutionary psychology, David Buss, Leda Cosmides, Martin Daly, John Tooby and Margot Wilson, thank you. They bought into this quote here by Theodosius Dobzhansky, nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution and thank goodness they didn't because this field is contributing a lot to our understanding of human behavior. What are some of my concluding remarks? Well, the idea of applying evolutionary theory to psychology is not a new one and certainly, not new to think about in terms of mental health either. But understanding the adaptive problems that are cognitive mechanisms were designed to solve, we can gain more insights, deeper understanding into why we behave the way we do and why we think the way we do. For example, our ability to recognize and avoid potential threats was likely shaped by natural selection over time. If we don't have a spider phobia ourselves, we know someone who does or if you don't have a snake phobia, you know someone who does. If you think about ancestral environments and I know there are environments maybe not close to you, but there are environments outside of Western world and some areas even in the United States, where there might be more risk of a poisonous spider or a snake being close by, but for the most part, we don't encounter that very much yet we still have these mechanisms in mind that direct us to be startled or to have outright phobia towards these types of poisonous animals, even in our modern environment. Without an evolutionary perspective, psychology can seem like a disjointed collection of unrelated subfields and I would say that not seem like, but I think it appears that way. Evolutionary approaches allow for us or a better way of thinking about the complex nature of our human behavior. It's a lens with which we can use to think about why we are the way we are. From that we can reap the benefits of progress by applying this framework to our psychology, including mental health issues and serious social problems like deliberately killing oneself. We can read these benefits of progress just as the biological sciences have for decades now. There is no biology, there's no understanding of biology without evolution by natural selection, understanding how that works. The argument here is that there is no reason, or at least no reason that I can think of or that I have seen [LAUGHTER] that we should not apply evolutionary thinking to understanding and making more progress in understanding our human nature. Ultimately, Darwin's theory of natural selection provides a powerful theoretical framework within which to organize all of psychology instead of looking at these disjointed collections of understanding, so there's a developmental understanding, social, a cognitive inherent to a evolutionary framework is this idea that it's not just a genetic explanation. We understand that there's this interactive relationship between genes and environment.

By considering ways in which our evolutionary history has shaped our minds and behavior, we can gain a deeper understanding of what makes us human. I'd like to leave you with a quote. It doesn't seem right to not include this quote if we're talking about evolutionary psychology. This is a quote taken from origin of species by Charles Darwin, "in the distant future, I see open fields for far more important researches, psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation, light will be thrown on the origin of man." This was 1859 and here we are still talking about this and this quote is totally relevant today. I'm ending the talk with a addition to the quote [LAUGHTER] that I included earlier in the very beginning of the presentation, "acquiring knowledge is a conversation not a destination." "Let us meet here again tomorrow", was also included as part of this quote in Jonathan Raunch, The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth and this was a quote that he used from Aristotle.

It captures the way that I think about understanding science and its application and just knowledge in general that it's a conversation on a destination. Even for topics as difficult as mental health issues and if we are not depressed or anxious ourselves, we know someone who is, but one of the outcomes or one of the things that are tied into those discussions is things like suicide. While I don't have all the answers and I don't think anyone does at this point, it's certainly worth a conversation and we don't want that conversation to be the last conversation. It's not something that ends. We can always understand things better. Let us meet here tomorrow. Let us meet here again tomorrow. If you are interested in learning more about any of these topics, please feel free to reach out to me. I will include some contact information for myself, also, for the Department of Psychology and then for the Center for Evolutionary Psychological Sciences. I welcome any feedback and thank you so much for your time, and I hope that you enjoyed my presentation.

- Promote collaborative evolutionary psychological research within and across colleges and schools at OU, and with faculty and students housed at other universities, nationally and internationally.

- Provide educational opportunities in evolutionary psychological science (e.g., weekend seminars, summer camps, academic minor, certificate program) for faculty, students, staff, and community members at OU, as well as nationally and internationally.

- Develop educational and financial partnerships with local and regional businesses (e.g., Reproductive Associates of Michigan).

- Develop educational and financial partnerships with scholarly publishers of academic journals and books (e.g., Oxford University Press, Springer Nature).

- Provide seed funding to support an initial phase of innovative research projects to increase the probability of external funding; separate funding mechanisms to support graduate student research and faculty research.

- Organize and host visits and lectures by distinguished evolutionary psychologists, intended for and open to broad audiences, including faculty, staff, and students at OU, and local and regional community colleges and universities, as well as community members.

- Organize and host bi-annual international and interdisciplinary conferences showcasing the intellectual value and promise of an evolutionary perspective on topics and themes of longstanding human interest, including death, sex, morality, psychopathology, and violence; conferences are two-day events featuring as panelists 10-15 leading scholars from around the world that begin with a keynote lecture open to a broad audience, including faculty, staff, and students at OU, and local and regional community colleges and universities, as well as community members (see oakland.edu/psychology/conference).

- Other activities that will help to enhance evolutionary psychological science.

Todd K. Shackelford, Founding Director (Distinguished Professor and Chair, Psychology, OU), 2021-2026

Viviana A. Weekes-Shackelford (Special Lecturer, Psychology, OU), 2021-2026

Virgil Zeigler-Hill (Professor and Director of Graduate Training, Psychology, OU), 2021-2025

Melissa M. McDonald (Associate Professor, Psychology, OU), 2021-2024

Lisa L.M. Welling (Associate Professor, Psychology, OU), 2021-2024

Brandy A. Randall (Professor of Psychology, Dean of Graduate School, OU), 2021-2023

The Steering Committee members include the Director and 3-4 additional Oakland University faculty members. In addition, the Steering Committee will include one current OU administrator as ex officio member, appointed for a two-year term, renewable for no more than two terms. Steering Committee members are appointed by the Director for a term of five years, and advise the Director on all Center matters, including research, instruction, service, and community engagement.

Department of Psychology

- Martha Escobar, Professor

- Melissa M. McDonald, Associate Professor

- Todd K. Shackelford, Distinguished Professor and Chair

- Jennifer Vonk, Professor

- Viviana A. Weekes-Shackelford, Special Lecturer

- Lisa L.M. Welling, Associate Professor

- Virgil Zeigler-Hill, Professor and Director of Graduate Training

Department of Philosophy

- Paul Graves, Associate Professor

- John Halpin, Associate Professor

- Mark Rigstad, Associate Professor

Department of Biological Sciences

- Scott Tiegs, Professor

- Fabia Ursula Battistuzzi, Associate Professor

Department of Linguistics

- Samuel Rosenthall, Associate Professor

Internal Advisory Board members include the Director and members of the Steering Committee, along with full-time or part-time faculty members affiliated with Oakland University. Internal Advisory Board members are appointed by the Director and advise the Director and Steering Committee on all Center matters as requested by the Director, including research, instruction, service, and community engagement.

Joshua Ackerman, University of Michigan, USA

Laith Al-Shawaf, University of Colorado, Colorado Springs, USA

Jeanette Altarriba, University at Albany, USA

Kevin Beaver, Florida State University, USA

David Benatar, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Laura Betzig, University of Michigan, USA

David Bjorklund, Florida Atlantic University, USA

Brian Boutwell, University of Mississippi, USA

Sarah Brosnan, Georgia State University, USA

Kingsley Browne, Wayne State University, USA

Martin Brüne, Ruhr University Bochum, Germany

David Buss, University of Texas, USA

Joseph Carroll, University of Missouri—St. Louis, USA

Lei Chang, University of Macau, China

Jerry Coyne, University of Chicago, USA

A.J. Figueredo, University of Arizona, USA

Bernhard Fink, University of Vienna, Austria

David Geary, University of Missouri, USA

Mhairi Gibson, University of Bristol, UK

Eileen Hebets, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, USA

Leif Edward Ottesen Kennair, Norwegian University of Science & Technology, Norway

Douglas Kenrick, Arizona State University, USA

Daniel Kruger, University of Michigan, USA

Norman Li, Singapore Management University, Singapore

Dario Maestripieri, University of Chicago, USA

Jon Maner, Florida State University, USA

Rose McDermott, Brown University, USA

Randy Nesse, Arizona State University, USA

Michael Bang Petersen, Aarhus University, Denmark

Steven Pinker, Harvard University, USA

Stephanie Preston, University of Michigan, USA

David Puts, Pennsylvania State University, USA

James Roney, University of California—Santa Barbara, USA

Catherine Salmon, University of Redlands, USA

David Schmitt, Brunel University, UK

Cas Soper, Independent Scholar, Portugal

John Teehan, Hofstra University, USA

Randy Thornhill, University of New Mexico, USA

Paul Vasey, University of Lethbridge, Canada

Jerome Wakefield, New York University, USA

Katie Zejdlik, Western Carolina University, USA

External Advisory Board members include leading national and international scholars with expertise in evolutionary psychological science. External Advisory Board members are appointed by the Director and advise the Director and Steering Committee on all Center matters as requested by the Director, including research, instruction, service, and community engagement.

Department of Psychology

654 Pioneer Drive

Rochester, MI 48309-4482

(location map)

(248) 370-2300

Fax: (248) 370-4612